‘The city as a form of settlement did not arise by chance. The city is the richest economic and cultural form of community settlement, proven by centuries of experience. In its structural and architectural design the city is an expression of the political life and the national consciousness of the people.’

– Government of the German Democratic Republic,

The Sixteen Principles of Urban Design (1950)

Architecture is the political art par excellence, and not only because, unlike painting or literature, architecture is a collectively consumed art, and therefore constitutes its audience as a mass, rather than fragments it into the individual consumer. From this collective consumption, undoutedly, derives its social power to constitute a community of interest – with common goals, a shared history, and a collective future – from an undifferentiated and therefore potentially revolutionary society. ‘Architecture or revolution!’ was Le Corbusier’s warning to the bourgeoisie – and he was right. But in addition to this power, which it shares with music and theatre – which are themselves dependent upon the architecture of their setting – architecture goes beyond the symbolic realm to mobilise the actual referent: the human body. At once receptacle, vehicle and medium for the human mind, the human body is captured, subjected, moved, orchestrated, arranged, placed, situated, presented, configured and collectivised by architecture as a mass. Whether it is the willingly embraced community of the music festival, sports arena or religious event, or the enforced collectivity of the shopping mall, the rush-hour traffic jam or the public transport queue, this mass remains the object of political government, and architecture is the art that fashions that object: in the spaces of our dwelling, our labour, our consumption, our play, our entertainment, our celebration, our anxiety, our fear, our anger, our collective participation in the spectacle of society. Indeed, the increasing virtuality of our communities has only increased our nostalgic longing for architectural massing. To understand how this political object is constituted and deployed, governed and interrogated, controlled and dispersed, we should attend to the technique of architecture; for it is this technique, in the broadest sense of the term, that will reveal to us the ethics of the politics it serves. Architecture is always political.

1. Demolition and Forgetting

Official policy in Germany is to ‘de-Nazify’ the past, ostensibly in order to remove sites of pilgrimage, memorial and potential revival for the far-right. In Berlin’s Olympic Stadium, accordingly, built for the 1936 games, the names of the medal winners – including, to Hitler’s annoyance, the Afro-American athlete Jesse Owens – are still there, written in inlaid metal on the walls at the great west entrance through which Der Führer entered the arena. Hitler’s name, however, has been removed, leaving a large, noticeable gap on the south wall. In contrast, the name of the architect, Werner March, has been left. This absence has now become another kind of site – of tourism, forgetting, gloating – for Western tourists, who without exception (we were no exception) photograph the absent name of Adolf Hitler.

The policy of de-Nazification was initiated by the Allies immediately after the fall of Berlin in 1945, and following the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989 it has been extended to a similar but unofficial process of ‘de-GDRfication’, with numerous statues of Lenin demolished, streets previously named after the heroes of Marxist-Leninism renamed or reverting to their previous names (often from Germany’s imperialist past), and GDR government buildings pulled down as unsightly reminders of Germany’s colonisation by a foreign power and alien ideology imposed by the now fallen Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. Among the victims of this policy was the 63-foot statue of Lenin that was erected in Leninplatz in 1970 on the hundredth birthday of the leader of the Soviet Union. This was pulled down in 1991, a bare year after unification, its head buried in a wood on the outskirts of Berlin, and the square renamed the United Nations Square. Another was the Palace of the Republic, opened in 1976 to house the GDR parliament on the site of the demolished Berlin Palace, and which was itself demolished in 2006. The fact that the German Democratic Republic was not part of the Soviet Union but a satellite state run and administered by Germans from 1949 seems to have been as conveniently forgotten in post-unification Germany as the fact that Hitler’s National Socialist German Worker’s Party received nearly 44 per cent of the vote from the German people in 1933. Both political systems, in the German Federal Republic’s revisionist account of history, have been similarly (if not equally) erased and forgotten as examples of ‘socialism’, with little distinction made between monuments to its national or soviet versions.

For the sake of comparison, I suppose an equivalent policy in the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland would be to knock down every Victorian civic building, town hall, museum, market square, and perhaps street terrace and municipal garden (we have already demolished or shut down the docks, mines and industries, turned the warehouses into luxury housing and the power stations into galleries), condemning them as unwanted reminders of our colonialist and imperialist past – of the occupation and exploitation of India for two hundred years, of the enforced opium trade with China, of the genocidal slave trade with Africa, of the man-made famines in Ireland, India and Malaysia, of the Boer and Kenyan and Malay and Cypriot concentration camps, the Yemen torture centres, the violent and cynical suppression of Arab liberation, and all the other myriad crimes perpetrated by the British Empire as it reached out its iron fist to squeeze the human and material resources from which our Victorian cities were built.

But citizens of the Federal Republic of Germany might argue: the GDR regime was imposed on its own people, not on a colonised other, and to retain its civic and military monuments, above all, if not its state-built housing, implies that something of value may be rescued from a system of socialist oppression antithetical to the German people, if not humankind itself. To which I would respond: and what of the generations after generations of the British working class that laboured in field, factory and mine in conditions of wage slavery remunerated by their barely continued existence as beasts of burden on whose backs the British Empire accrued its industrial wealth at the cost of the semi-enslavement of 90 per cent of its own people? Is this not a system of capitalist exploitation compared to which the 40-odd years of the GDR cannot compare in brutality, oppressiveness and the crushing of human potential? If we were to follow suit, and erase every last monument to the production of poverty and inequality on which the UK has been – and continues to be – built, what building would be left standing in the British Isles?

But while, for better or worse, Germany has renounced its socialist past – and not just the deformed version under which East Germans lived for four decades – in the UK we continue to embrace the capitalist system that subjected and continues to subject both our own citizens and, in far greater numbers, the citizens of other countries across the globe to economic exploitation, political homogeneity and ideological hegemony that has turned both them and us into the willing subjects of late capitalism. And much as the Federal Republic of Germany is with the former German Democratic Republic, in the UK we are intent on demolishing the last traces of socialism in what’s left of our post-war welfare state, not only its welfare system, its national health service, its free education, its nationalised railways and heavy industries – all of which have been privatised by successive governments over the past 40 years – but also its housing, with less than 8 per cent of the UK population living in council housing today compared with 42 per cent in 1979.

2. Memory and Reconstruction

Dresden, however, presented a slightly different response to German unification to that in Berlin. As the capital of Saxony and one of the major cities of the former East Germany, the unofficial policy of ‘de-GDRfication’ has not been as ideologically pursued as it has in Berlin. Dresden, of course, was largely burned to the ground by orders of RAF Bomber Command – another crime of the British Empire – which between 13 and 15 February 1945 destroyed over 1,600 acres (6.5 km2) of the city centre, killing up to 25,000 people as a result of the firestorms that swept through much of the city, and leaving nearly 12,000 dwellings gutted in its wake. When the GDR took over the administration of Dresden in 1949, therefore, it was faced with a blank canvas on which to rebuild the former stronghold of the German bourgeoisie as an industrial centre in the socialist workers’ and peasants’ state. Some of the ruins of churches, royal buildings and palaces, such as the Gothic Sophienkirche, the Alberttheater and the Wackerbarth-Palais, were demolished in the 1950s and 1960s rather than being repaired; but others, such as the Zwinger Palace and the Semper Opera House, both in the Old Town, were faithfully reconstructed to their former Baroque glory, with the former opened to the public as early as 1951, and the latter finally completed in 1985. By contrast, the ruins of the Frauenkirche were left standing as a memorial to the war

Most areas, however, were cleared of rubble and rebuilt in the 1950s and 1960s modernism of the GDR. The eighteenth-century boulevard of Hauptstraße, for instance, which runs for 400 metres through the New Town on the north bank of the River Elbe, was reconstructed between 1974 and 1980, during which it was pedestrianised and lined with 1,000 prefabricated homes for workers and renamed Straße der Befreiung (‘Street of the Liberation’). History came full circle in 1991, however, when following unification it reverted back to plain old ‘High Street’, since when the chain stores and tourist bars of late capitalism have moved in. The proletarian housing is still there, though whether it houses workers or has been colonised by Dresden’s hipsters I don’t know.

Alongside the subsequent programme of ‘de-GDRfication’ (Dresden’s authorities removed its own statue of Lenin from Wiener Platz) there ran – and is running still – a programme of restoration and reconstruction. The Frauenkirche, for instance, and its memory of the Great Patriotic War (as the Soviets referred to the Second World War) has been reconstructed. Some of this reconstruction, as we have seen, began under the GDR; but since Die Wende (The Turn), as the Germans refer to the transition to today’s Federal Republic of Germany, the undifferentiated past that ran up to the foundation of the Third Reich now includes the German Democratic Republic that succeeded it in East Germany. However, under the GDR, buildings reconstructed in the Old Town had been kept to the same plan and elevation as the lost buildings, but reinterpreted according to the construction methods of modernism and the design principles of the socialist state as laid out in The Sixteen Principles of Urban Design that were the primary model for urban planning in the GDR between 1950 and 1955. Under the capitalism of post-Wende Germany, in contrast, a policy of architectural pastiche has been instigated, according to which eighteenth- and nineteenth-century buildings have been reproduced using modern materials and construction methods, with cast concrete standing in for carved stone, steel frames with stone panel facades for load-bearing stone walls, and aluminium for wooden frames. The result are pixelated, Lego-block versions of the original buildings, resembling models on a war-gaming board or train diorama.

More recently, though, there appears to have been a return to a form of interpretation not entirely dissimilar to that attempted under the GDR, where the footprint, elevation and proportions of the ‘original’ – that is, lost – building is retained but reinterpreted – not, as it was under the GDR, according to the design principles of modernism, but according to those of postmodernism. Strictly speaking, though, this is a misnomer, as postmodernism is defined by the absence of design principles; or, rather, the absence of a determining set of principles, in place of which postmodernism picks and chooses from the past and the present, from the international and the vernacular, which it quotes in a melange of influences. Postmodernism, in other words, is always already an act of reconstruction and reinterpretation, from which derives its elusive and contested politics. When reconstructive, postmodernism leans towards (or explicitly serves) a conservative, retrogressive, even reactionary politics; when interpretive, it is at best critical (although never, as modernism was, utopian), more often ‘playful’ (usually as an apology for its embrace of commercialisation), and at worst spans the self-indulgent disasters of the 1980s and 1990s all the way up to the timid, derivative, weak, bland, unimaginative, back-of-a-napkin, so-called ‘London vernacular’ we see dominating new developments in the UK capital today.

Interestingly, all these architectural approaches can be seen on Schloßstraße at the heart of the Old Town. Where it is crossed by Sporergaße, a former GDR carpark has been dug up, and the foundations of the old city have been exposed – I don’t know whether as a memorial or as preliminary to the redevelopment of the land. To the west of this square, on Schloßstraße, is a line of GDR buildings that interpret its Baroque predecessors along modernist lines. On the northwest corner is the reconstructed Residenzschloss – transformed now into a museum. To the north, on Sporergaße, is a line of truly hideous post-unification Baroque pastiche’s that wouldn’t look out of place on a model train set. And to the east, on Schößergaße, alongside another pastiche, is a recently completed postmodernist interpretation of the Baroque model. All three sides of the square are of the same height and have steeply pitched roofs, but the principles of their reconstruction – restoration, interpretation, pastiche and memorial – come out of different architectural approaches to the past, the present and the future in which their politics are clear to see.

3. Refurbishment and Reevaluation

This doesn’t mean, however, that Dresden’s GDR buildings are all being demolished to make way for postmodern pastiches of their Baroque predecessors. Nearly every GDR-era building we saw has been – or is in the process of being – refurbished; and those awaiting refurbishment revealed how much they had been neglected of maintenance and allowed to fall into disrepair – a common enough sight in the UK. But rather than demolishing them – as their council-estate equivalents are being demolished in their tens of thousands in the UK – Dresden’s GDR housing is being systematically refurbished and, in some cases, added to.

The refurbishments we saw consist largely of cladding, sometimes of the addition of balconies (although most GDR housing seems to have had these), and the addition of rendering and decorative paint jobs. One would imagine equivalent refurbishment measures are being taken to the interiors, much in line with our stalled programme of bringing council flats up to the Decent Homes Standard, but the only interior we saw was the Brutalist former GDR military housing in which we stayed in Dresden’s New Town.

The additions included roof extensions to some blocks – again, much in line with ASH’s design proposals for the increase in housing capacity on London estates threatened with demolition. This was fairly rare, though, as most of the GDR blocks we saw in Dresden were already fairly lofty.

But we saw a row of 10-storey blocks, set back at a tangent to St. Petersburger Straße (presumably the former Leningrader Straße) to the east of the Old Town, that were in the process of having winter gardens attached to their ends, much as has been done with equivalent post-war residential blocks in the banlieues of Paris by Lacaton and Vassal, whose motto – ‘Never demolish, never remove or replace, always add, transform, and reuse!’ – is exemplary of the approach the UK needs to take if we are to stop the mass demolition, privatisation and redevelopment of what’s left of our own post-war housing estates.

One of the most successful aspects of the GDR housing we saw in Dresden was the town planning. Johannstadt, a suburb to the south-east, suffered some of the worst bomb damage and was largely rebuilt in the 1970s when construction in the GDR reached its highest level, completing over 2.1 million flats. The two residential complexes of Johannstadt-Nord and Johannstadt-Süd are built in a variety of housing typologies that, crucially, are interspersed with the infrastructure such housing needs to function as a town.

This new infrastructure included not only a new street plan – one more in keeping with the modernist blocks and served by trams – but, along Pfotenhauerstraße, a clinic, a school, gardens, a town square, a sports club, a row of shops and, at its eastern end, a technical university and public hospital.

Again, where nineteenth-century terraced housing has survived the bombing or been restored from fire damage, the adjacent GDR buildings follow the same alignment, plan, elevation, and even attempt an imitation of their pitched roofs. Across the way, by contrast, the modernist blocks rose to 10 stories and more.

It’s hard to judge a neighbourhood by a single visit, but when we walked through Johannstadt-Nord it seemed a successful and happy place, clean, with many people on the street, the schoolchildren cheeky but polite; a youthful community with no sign of systemic poverty, rough sleeping or crime. And we didn’t see a cop all day.

True, the square between Pfeifferhannstraße and Bundschuhstraße, which is bounded to the west by a nineteenth-century terrace and completed to the east and north by modernist blocks, has been infilled with a large, crudely designed, ALDI supermarket – a post-unification taster of the joys of capitalism, no doubt; but otherwise the GDR town plan has been retained and respected. Between them, the residential complexes of Johannstadt-Nord and Johannstadt-Süd supply over 6,300 dwellings – more than double the size of London’s Aylesbury estate, which Southwark council are currently demolishing because apparently they can’t afford to refurbish it.

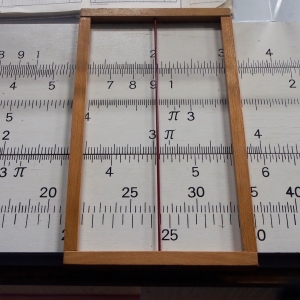

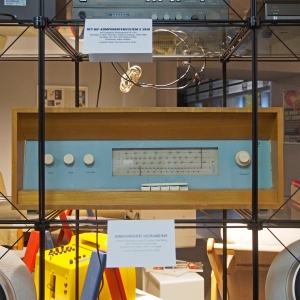

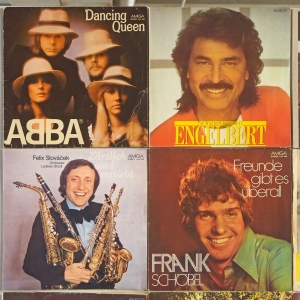

Significantly, we saw no museum anywhere in Johannstadt. Indeed, apart from a preserved prison used by the Stasi, there is only one museum in Dresden devoted to the GDR, and this was not about its political oppressiveness but about its daily life. Rather oddly, ‘Die Welt der DDR’ (The World of the German Democratic Republic) is located inside a shopping mall, and its contents are largely made up of the kinds of modern conveniences one would buy for home or work or play in the 1960-80s (there was little or nothing from the 1950s, which Germany spent recovering from the war). When we first entered I thought this was going to be an opportunity for contemporary Germany to mock its past, comparing the backwardness of GDR technology to those available in the shopping mall outside. But instead it came across – at least to me – as something of a celebration. Many of the products reminded me of my childhood in the 1970s; and although their brands were unfamiliar, their uses, styles and forms were not. From the cars and motorcycles to the kitchen appliances, home furnishings, children’s toys, garage tools, cash registers, medicine cabinets, clothes irons, typewriters, slide rules, calculators, transistor radios, sound systems, records, cameras, photographs, magazines and newspapers, it was like I was having my own UK version of Ostalgie.

This surprised me. Within the Western propaganda we call the entertainment industry, the Eastern Bloc is uniformly depicted as the other side of a borderline between affluence and poverty, the production surplus of West Germany’s US-funded ‘economic miracle’ and Stalinist queues around the block for bread; but if this is what material life was like in the GDR then it wasn’t substantially different to life in the UK, which unlike the Federal Republic was still paying off its war-debt to the USA until 2006. Only someone who lived through those years could say to what extent this exhibition is an accurate representation of life in the GDR, and perhaps it’s as true a reflection of working-class life as the UK’s 1951 Festival of Britain; but it’s hard to imagine an exhibition like this finding a place among the plethora of museums in Berlin, where the GDR of popular imagination is little more than an outpost of the Soviet Gulag.

In reality, however, and despite Western propaganda to the contrary, the new post-war housing in Germany was fairly similar in form and construction both sides of the Iron Curtain. With 3.6 million homes, some 20 per cent of the total housing stock, destroyed during World War Two, the necessity of housing the homeless population of Germany took primacy over architectural expressions of opposing ideologies. Built in East Germany by the state and in West Germany largely by not-for-profit and co-operative housing companies, in the unified Federal Republic of Germany today there are over 720 large housing estates with over 1,000 dwellings each – with more than a hundred of these having over 2,500 dwellings – providing more than 2.3 million homes and 7 per cent of the entire housing supply, the same percentage of council housing as there is in the UK today. In the former East Germany, where 380 such estates provide 1.5 million dwellings and 22 per cent of the housing supply, nearly 1 in every 5 households lives in a large housing estate; while in the former West Germany, with 340 large housing estates, it is 1 in every 15. By 2000, approximately 40 per cent of the housing estate stock had been refurbished and modernised across unified Germany.

4. Capitalism and History

On our first night in Dresden, we walked down to the Elbe by the Augustus Bridge, which is undergoing extensive refurbishment. At this bend in the river the south bank of the Elbe is steep, rising up to the famous ‘balcony of Europe’ and the Old Town beyond; but the north bank has a gradual incline, and between the water and the New Town is a flood plain that, when we were there, was over a hundred yards wide. Since the river can rise up to and – as recently as 2002 – overflow the south embankment, the floodplain is undeveloped and overgrown with grass, and when we walked down groups of Dresdeners were sitting in the dark, talking, drinking and smoking. On this particular night a stage with seating had been erected to the east of the bridge, and the Queens of the Stone Age were in town. I guess they’re exactly the sort of generic, head-banging, US rock the Germans find so inexplicably attractive, so we wandered over to look (if not to listen). The temporary arena had been fenced off, but on a hillock outside sat around a hundred people, vaguely drawn by the concert but not enough to pay for an entrance ticket. That’s not surprising. When I lived on the Gascoyne estate in Homerton, and every year watched Tower Hamlets council build a wall around the eastern section of Victoria Park so they could rent out the public land during the festival season, I and the equally impecunious used to sit on the raised children’s playground to the north and listen to the distant strains of Radiohead. What was surprising is that, whereas in London we were chased away by the police, here in Dresden a temporary bar had been set up outside the perimeter to serve the ticketless crowd. We bought some beers and sat down in the long grass, and as I looked around me in the dark a big smile began to crease my face.

It took me a while to work out why this felt so different, but eventually it dawned on me. There were no security guards telling me where I could and couldn’t sit, no fenced off strip behind which smokers were corralled, no armed cops shining torches into our faces, no sniffer dogs searching for drugs, no body checks for the ticket holders going in, no security cameras recording our every move as we sat there enjoying this tiny bit of freedom. In fact, during the whole week we were in Germany we saw cops only once, gimped up in bullet-proof vests, assault rifles and German Shepherds in the Berlin Alexanderplatz station, but that was the only time. I’m not for a moment suggesting that the German police are any less violent, any less unaccountable to the public, any less immune from prosecution than the British police. I was in Berlin in July 2016 when an army of them descended on the squats on Rigaer Straße, and they’re as brutal and militarised and in the service of corporate interests as our own cops. But it simply wouldn’t be possible to be in London for a week without being overwhelmed at every turn by the ubiquitous presence of the police in our public life.

Three weeks before we left for Germany we’d gone to see Nick Cave and the Bad Seeds at Victoria Park, and as usual a high, grey, temporary wall had been erected around a huge swathe of the park, removing far more of it than I remember from public use, and resembling nothing so much as the Berlin Wall. The entrance to the event was as policed by security guards, armed squad cars of police, sniffer dogs, body checks, bag searches and electronic screenings as entrance to a UK airport. As chance would have it, we were with a German friend of ours who lives in Berlin, and she was astonished by the level of intrusion and security for a music festival. To be honest, so was I, as I generally stay away from these kinds of corporate events for just this reason (that, and their ridiculous price tags). But sitting outside the gig on the north bank of the Elbe around midnight, when the local population showed no signs of returning home for a good night’s sleep before rising early to do whatever Dresdeners do for a living when they’re not hanging our in cafes, it struck me how accustomed we are to accepting without question the regulation, surveillance and policing of every aspect of our lives in the UK, where every piece of land is fenced off by our councils, priced up by developers, sold off to offshore companies and guarded by private security companies; where every movement across that land is scrutinised by guards, recorded by CCTV, directed by police, restricted by laws and charged for by investors; and just how much we’ve come to resemble the sheep we are when we’re corralled through those switchback fences that direct us through music festivals, sports events, airport security and every other form of public massing.

The purpose of travel, it is said, is to broaden our horizons. To that cliché might be added: and to recognise how much has been lost to the increasingly narrow horizons within which we live, how inured we’ve become to that diminution of our freedom, how easily and willingly we have relinquished our field of vision, how readily and eagerly we’ve given up even the hope of another world. As well as an economic system and a way or ordering nature, Capitalism is also a historical project, and to justify the vast inequality, exploitation and poverty it produces under the guise of ‘the best of all possible worlds’ capitalism has to do two things. First, it has to argue that the infinite variety of contingencies that compose the present are somehow the only possible combination, and that anything else – any deviation, any alternative, any change except more of the same – would spell immediate disaster for the world as we know it. Second, in order to back this argument, capitalism has to rewrite history, not only the immediate history of its past, but all history, so that its every strand is subjected to an evolutionary logic.

To make the contingency of the status quo look inevitable, the rule of thumb is to ground it in nature. Within the history of the world capitalism teaches its subjects, feudalism, for example, represents an ancient but superseded line, something like Homo Heidelbergensis in the evolution of the homo genus; socialism, by contrast, is a primitive and doomed line that rightly ended in extinction, something like Homo Neanderthalensis; while capitalism is the realisation of the dominant strand of the homo genus, something that was in us from the beginning, not only within us but driving us forward, compelling us constantly to supersede ourselves, separating us from evolutionary dead ends, flowering in the emergence and great march of Homo Sapiens, and reaching its apotheosis in Europe’s Cro-Magnons (which, significantly, wiped out Neanderthal man). History is far more than the writing of the victor erasing the past; it is the sublation of that past in the present, which is always now, always inevitable, always the only possible outcome of all hitherto history.

‘Who controls the past’, George Orwell famously wrote in 1949, ‘controls the future: who controls the present controls the past.’ Orwell was describing something like the GDR, which was founded the same year he published 1984; but his words more accurately describe our present. Why else does capitalism devote so much of its cultural resources to the telling of that history in television series, films, museums and, yes, even in novels? When my return flight from Berlin-Schönefeld was delayed I had time to walk around the single book shop that was left after passing through security, and I came across a copy of a new novel titled The President is Missing. A review of it in that month’s London Review of Books, which was waiting for me back in London, revealed it to be an apology for extraordinary rendition and extrajudicial killing whose co-author, surprisingly, is none other than Bill Clinton, the former President of the USA. Perhaps that’s not so surprising after all. For some time now Hollywood has been little more than the ideological arm of the White House and the Pentagon, so why not the market in airport fiction too? In this respect, Berlin, which sits along the most dangerous fault line in capitalism’s recent history, is the model contemporary city, not because of its contemporaneity (it is radically enclosed in its past) but because the entire post-unification city has been devoted to the telling of the history of capitalism’s greatest triumph over adversity. And like any Hollywood film, that history is almost entirely fictional. But this is the role of capitalist propaganda: not only – as that of the Soviet Union was – to erase that past behind the airbrush of the censor, but also to rewrite that history as the tragic predecessor of our triumphant present.

The 3.5 tonne head of Lenin they buried in the forest outside Berlin was dug up in 2015 for an exhibition in the suburb of Spandau. But before that, in 2003, the removal of the statue was restaged in Good Bye, Lenin!, the film comedy about the last days of the GDR. And in 2013 construction began on a replica of the Berlin Palace on the land cleared of the Palace of the Republic. Three of the facades and one of the interior courtyards are to be exact copies of the Baroque original, with the final façade, facing the River Spree, a postmodernist interpretation that repeats their elevation, floor and window lines on a modernist grid. The new building, called the Berlin Palace/Humboldt Forum, will, of course, be a museum. In the historical narrative written to justify this pastiche – and which the visiting public has been able to read in promotional material and on site, complete with a model of the pre-GDR Berlin, since construction began – no mention is made of the years of the Third Reich, and barely a single photograph was reproduced of the demolished Palace of the Republic. Instead, visitors are given a purely formalist chronological account of the additions and deletions to the architecture of the palace from the time of its construction as a Medieval castle in 1443, through its reconstruction as a Baroque palace in 1698, all the way up to the fall of the German monarchy in 1918 and its transformation into a museum. No mention, at all, is made of the revolution that brought the monarchy down and founded the German Republic. The last hundred years have simply been erased, and Germany’s Imperial past rewritten as a succession of architectural styles culminating in the genuine fake of the Berlin Palace.

5. Twilight of the Idols

Notwithstanding the religiously faithful reconstructions of the Zwinger Palace, the Semper Opera House and the Church of Our Lady – which I imagine most tourists, understandably, think are the originals – the most interesting building we saw in Dresden was the Palace of Culture. This is the architectural equivalent of Berlin’s Palace of the Republic, and the best chance we had of seeing what the latter might have looked like.

Completed on the north side of Dresden’s Old Market Square in 1969, the Palace of Culture escaped demolition by the German Federal Republic, was refurbished for fire-safety in 2007, listed in 2008 and closed in 2012 for renovation, which was completed in 2017.

Built around an internal, open staircase leading to balconied foyers, it houses a concert hall and a public library. On the first floor is a large mural painted on crude chipboard titled Our Socialist Life. Socialist realist in content but influenced in its formal language by the late work of Pablo Picasso, I liked it far more than the more famous mural, titled The Path of the Red Flag, on the building’s west facade, which in form if not in content reminded me of the kind of religious frescos you’d find in Dresden’s Baroque churches.

Here, in contrast, a central sunburst from which a white bird emerges illuminates the path of science to the right and of the arts to the left. The former passes through the study of physics, chemistry and technology to a rather whimsical image of two astronauts, male and female, holding hands as they swim through space like two of Marc Chagall’s lovers.

The mural, which bends back on both sides around the foyer corners, concludes on this path with the image of a Soviet satellite exploring space. Interestingly, on the other side, the path of the arts, which passes through music and painting, concludes with a crumbled – or perhaps smashed – statue lying on its side, a sort of Twilight of the Idols from which communism was meant to rescue humankind.

Halfway along this path, however, is an image of three figures, consisting of two men – one with a trowel, the other with a red flag – and a third, female figure, standing between and in front of them. In her left hand she holds a brick, in her right a stone hammer. She’s pretty, certainly, with whisps of brown hair falling out of her socialist worker’s headscarf, and her pose has something of a Madonna about it; but not only is this an image of woman as worker, as manual labourer, as technician – perhaps even as architect – but all these activities find an equal place in this mural with the finer arts of painting, music and poetry. Most of all, the focus of their depiction here is not the finished work, but the action of realising those works in the world. It reminded me strongly of a similar image of a female architect instructing a male worker that is carved in bas relief in one of the stations of the metro in the former city of Leningrad.

Outside, we walked across the Altmarkt, where a discreet memorial to the bombings is inlaid in metal between the cobbled stones. On the east side was the first McDonalds and the first Starbucks we’d seen in Dresden. Going south down Seestraße, where the pastiches of Baroque facades opened out into glass and metal shopping malls, we crossed into Seevorstadt, and Prager Straße confronted us with the full stupidity of capitalism’s consumer society, with rows of retail outlets selling the useless commodities of our throwaway culture. Then another Starbucks. Suddenly it was like being back in London again.

Beyond, the residential blocks of the GDR were still standing, but covered now not only in cosmetic cladding, but also in the logos of hotels, chain-store retailers, corporate brands and the moronic billboards of capitalist identity. The modernist drum of the GDR cinema was almost lost behind a row of advertisements for Hollywood films and Pizza Hut. There was no trace of the giant statue of Lenin leading the workers that once stood at the south end of Prager Straße where it meets Wiener Platz. But there was another McDonalds.

At the corner of Waisenhausstraße there was also a branch of the US sports chain store Foot Locker. In the shop windows above the entrance was a series of large photographs repeating, with variations, a single image of a young girl, dressed in anything but sports clothes, standing in front of some vaguely military-looking buildings, and I was struck by how much her pose resembled that of the woman in the socialist mural. I guess she too is pretty, though she looked as miserable as every model in the emaciated, joyless world of fashion. But this girl was immobile, weighed down by the latest clothes not being sold inside, her hands empty and useless by her sides, with no relationship to or agency over the buildings behind her except as adornment and decoration, as image for the commodities she’s being used to sell.

Undoubtedly, the reality of the GDR didn’t live up to the murals it used to adorn its civic buildings, just as the images with which we decorate our churches, government buildings and high streets hardly describe Christian civilisation, parliamentary democracy or Western society; but between this vision of a socialist future and the corporate-military-surveillance complex that’s shaping our capitalist present I know which I prefer. All the identity politics in our politically correct world won’t make a dent in this hegemonic and multinational image of the capitalist subject as slavish consumer, as obedient worshipper at the altar of the commodity, as willing participant in the spectacle of capitalist society. And it never will, until we take the brick from the socialist worker’s hand and smash the mirrors in which we live out our looking-glass lives.

Simon Elmer

Architects for Social Housing

Architects for Social Housing is a Community Interest Company (no. 10383452). Although we do occasionally receive minimal fees for our design work, the majority of what we do is unpaid and we have no source of public funding. If you would like to support our work financially, please make a donation through PayPal:

Reblogged this on Wessex Solidarity.

LikeLike