Ivy House, a private hostel for homeless families by Manor House tube station, stands directly opposite the former Woodberry Down Estate, where 1,980 council homes were demolished when the current Hackney Mayor, Philip Glanville, was Cabinet Member for Housing. According to the Woodberry Down masterplan, which was granted planning permission by Hackney Labour Council in February 2014, these are being replaced with 3,292 luxury apartments for private sale, and 2,265 so-called ‘affordable’ units – that is, up to 80 per cent of market rate – of which a mere 1,088 have been promised for social rent. These proposed tenancies, however, are dependent upon future viability assessments – which means the profit margins of the developers.

Woodberry Down is being redeveloped by property developers Berkeley Homes and Genesis housing association, which according to Hackney Labour Council is responsible for delivering over 1,900 homes for social rent and shared ownership. However, in July 2015 Neil Hadden, the chief executive of Genesis, declared: ‘We are not able, or being asked, to provide affordable and social rented accommodation to people who should be looking to the market to solve their own problems.’ The Berkeley Group, which has the highest profit margins of any builder in the UK, recorded a 34 per cent rise in pre-tax profits to £392.7 million in the six months to the end of October 2016, up from £293.3 million over the same period the previous year. The Chairman of the Berkeley Group, Anthony William Pidgley, CBE, has a total annual compensation, made up of his salary, annual bonus and stock options, of £21.489 million.

Former council tenants on Woodberry Down estate who moved into the Genesis homes have complained that they have fewer rights as housing association tenants, receive worse service and pay much higher bills. And there are reports – particularly from pensioners and low-income families – of tenants having to go into debt just to afford the heating, or of moving out altogether because they cannot afford their increased rent, service charges and utility bills.

The women in the hostel across the road live in single bedsits with their children, and although Ivy House is categorised as temporary accommodation some families have been there for more than two years. They are allowed no visitors at any time, day or night, are not permitted to eat in their room, cannot smoke anywhere in the hostel, and are prohibited from using their own bed sheets. CCTV is fitted throughout, and there are regular room inspections by staff. One interviewed mother said: ‘I feel like I’m in a prison.’ Their entire Housing Benefit goes to the privately-owned hostel.

Ivy House, which has 97 bedsits over 2 floors, is owned by Rooms & Studios London, a company set up by business operations expert Danny Edgar and structural engineer and technocrat Zamir Haim. They have 1,500 units for rent across London, and describe the accommodation as being for ‘professionals, students and hostel seekers’. In the three decades they have operated in London the two entrepreneurs have bought, built, refurbished and sold assets worth over £200 million.

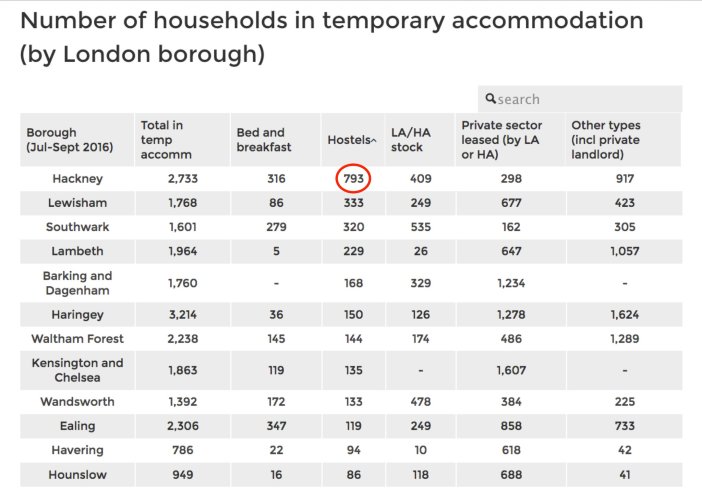

Hackney Labour Council currently houses 793 homeless families in hostels like Ivy House, the highest number of any London borough, where a total of 2,733 households, around 8,000 people, live in temporary accommodation, the sixth highest in London. £35 million per year in Housing Benefit is being paid to private landlords like Rooms & Studios London in order to house homeless families in temporary accommodation in Hackney – but it’s being paid by Central Government, not Hackney Council. It’s not surprising, therefore, that the Hackney Mayor recently stated he was ‘pleased’ he kept the borough’s hostels open.

Hackney Council isn’t alone. London Labour Councils lead the way in the number of homeless households they place in temporary accommodation, making up 10 of the 13 worst councils and accounting for 37,661 households out of a total of 53,343. That’s upwards of 150,000 people, including 90,000 children, living in temporary housing, bed and breakfasts, hostels and other private accommodation across London. Yet the programme of estate demolition – also led by London Labour Councils – continues.

According to figures released this month by the Department of Communities and Local Government compiled from the 2015-16 data returns of Local Authority Housing Statistics, 5,098 dwellings owned by London Labour Councils (out of a total of 6,139 across the capital) are sitting empty this winter. But in reality, given the number of council estates having their housing stock transferred to private developers and housing associations and then emptied – and left empty for years on end – in preparation for their demolition, these figures are only the tip of the iceberg.

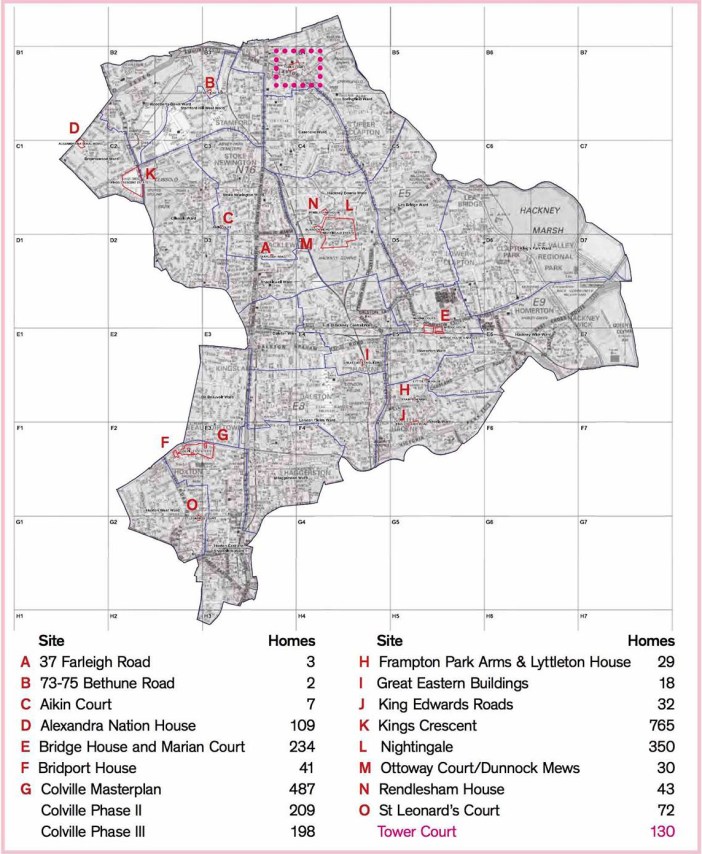

In the face of this housing crisis, Hackney Labour Council has recently announced the extension of its demolition programme to 19 council estates across the borough. This doesn’t include its collaboration with the Guinness Partnership in its plans to demolish Northwold Estate, whose council housing stock was transferred to the housing association. In place of the 19 demolished council estates, Hackney Council has said that it’s going to build 2,760 new homes: 1,360 for private sale, 500 for shared ownership or joint equity – about whose dangers residents are kept in the dark – with 900 homes promised for social rent.

What Hackney Labour Council doesn’t say, however, is how many council homes it will demolish across the 19 estates, how many residents will be made homeless by the demolition of their homes, how many will be able to afford to take up the council’s ‘Right to Return’ to the new developments, how many will be housed in privately-owned temporary accommodation for how many years within the borough, how many will be moved out of the borough under the threat of being declared to have made themselves ‘intentionally homeless’ (at which point, following the 2011 Localism Act, the council’s duty of care is now discharged), how many net homes for social rent will be lost to the estate demolition programme, or what guarantees it gives that the 900 homes for social rent it has promised will actually be built now that, with the changes to planning legislation under the 2016 Housing and Planning Act, there are no longer any obligations to do so. And you can understand why.

Architects for Social Housing