1. The List

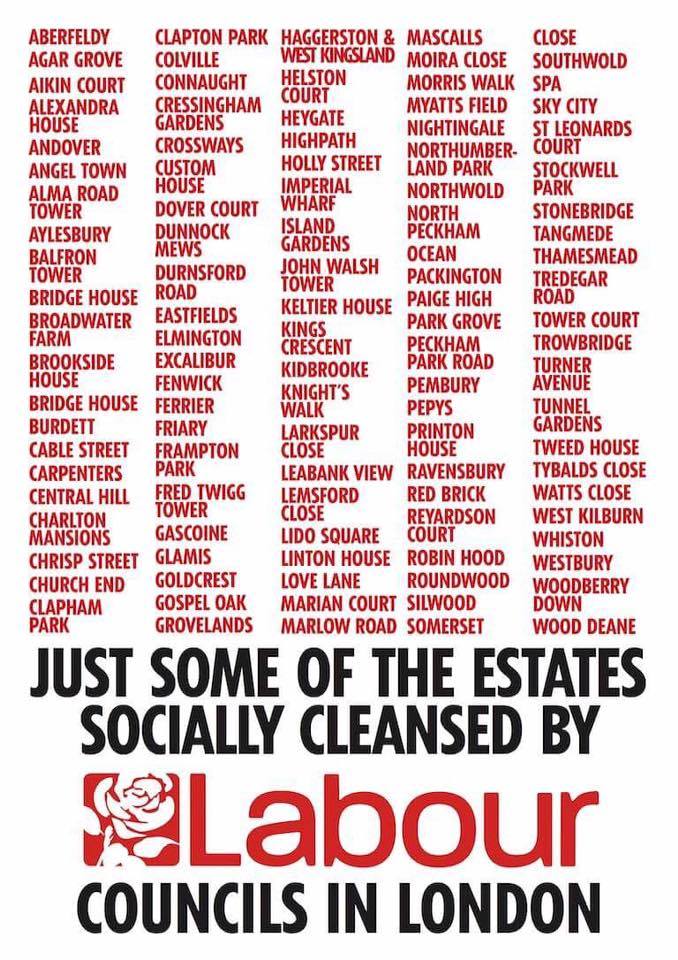

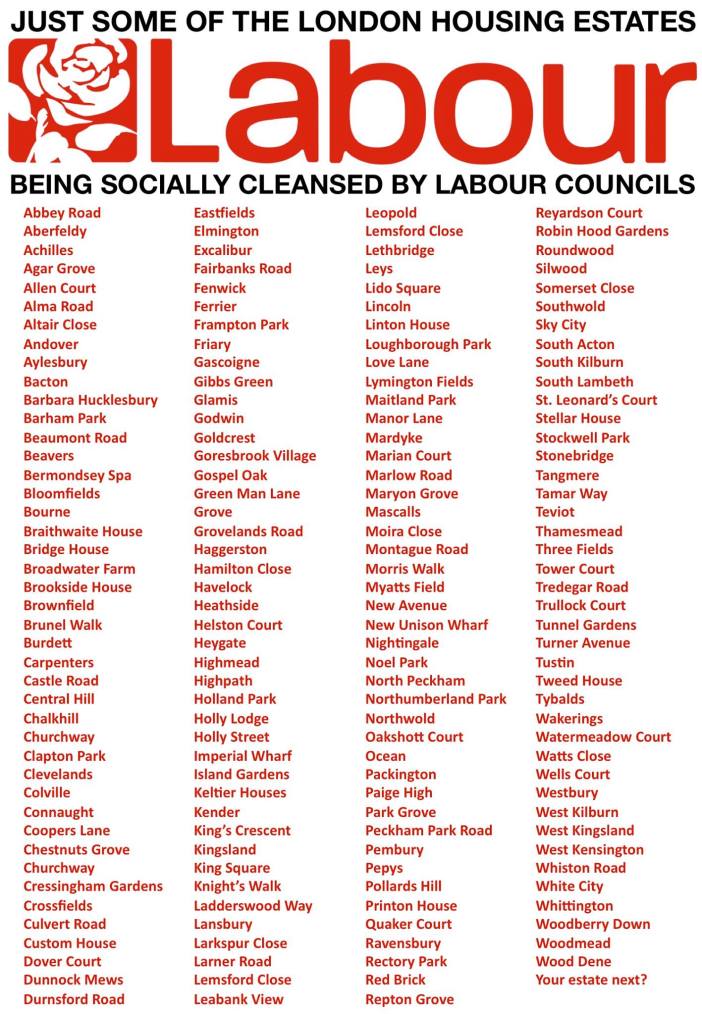

As I turned to camera and explained why I had just pursued first Sadiq Khan and then Jeremy Corbyn in opposite directions down the same Islington street, asking them questions they both resolutely refused to answer about their support for the estate regeneration programme being implemented by London’s Labour councils, a Labour activist stood behind me and held up a ‘Vote Labour’ placard, as if this would somehow compensate for the silence of the Party’s Leader and future London Mayor. At this point Sid Skill (not his real name, unfortunately) stepped forward and held up, in front of the Labour placard, an A3 sheet of paper bearing a list of about 40 names printed in red, below which was written in large black capital letters: ‘JUST SOME OF THE ESTATES SOCIALLY CLEANSED BY LABOUR COUNCILS IN LONDON’.

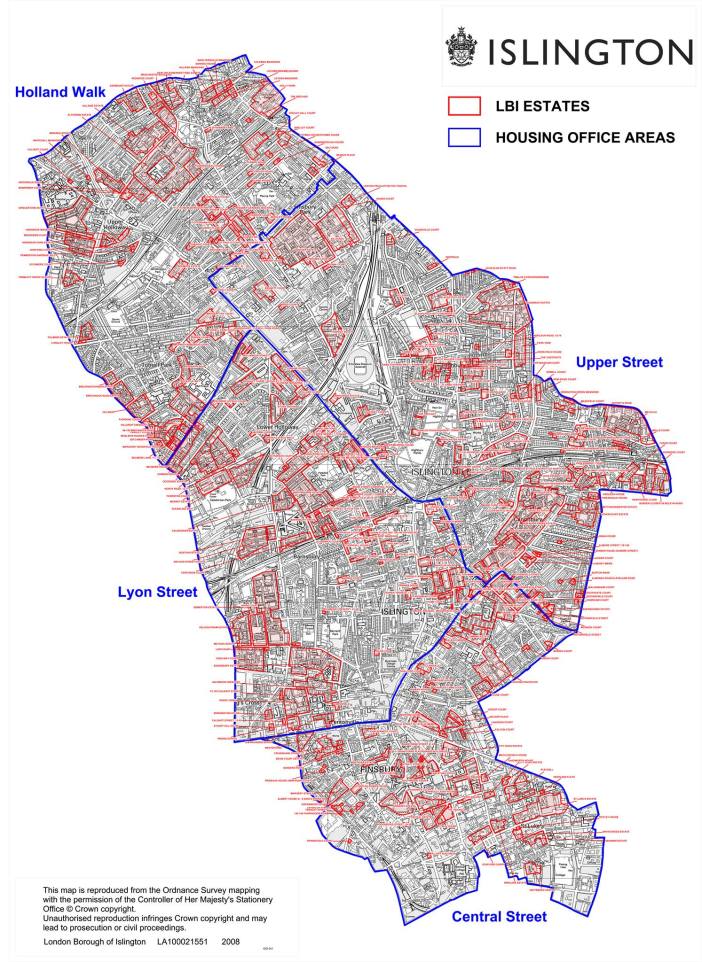

It was 26 March 2016, the elections for London Mayor were six weeks away, and we – that is, members of Architects for Social Housing, Class War, the Revolutionary Communist Group, several film crews and a bunch of press photographers – had just ambushed a publicity stunt designed to heal the public rift that had opened that week when it was revealed that the Labour candidate, Sadiq Khan, had appeared on another list of names, this one leaked to the press and identifying the MPs designated as ‘hostile’ to Corbyn’s leadership. I don’t think this was the first time I had seen the list Sid and L.G. had compiled and posted on ASH’s Facebook page, but it may have been the first time I had seen Sid use it as a weapon to combat the lies of the Labour Party. As I spoke to camera I held up another sheet of paper, this one bearing a map of Islington – the constituency of the Labour Leader who had just run away from me – on which every council estate had been outlined in red. I had taken this map from a report published in March the previous year by the Institute of Public Policy Research titled City Villages: More homes, better communities, which we had just exposed as the basis to the housing policies of both the Labour and the Conservative candidates for London Mayor. In this report the editor, the onetime Labour Peer, Andrew Adonis, had argued that the greatest source of brownfield land available for redevelopment in London is what Yolande Barnes, the Director of Research at Savills real estate firm and co-author of the report, estimated are the 3,500 existing council estates on which roughly 360,000 homes are built and in which over a million Londoners currently live.

It’s hard to say exactly when ASH had the idea of mapping London’s estate regeneration programme, but this is as good a moment as any; and I recall it here to distinguish our purpose in creating this map from a purely academic exercise that is content with recording the actions it maps but does nothing to oppose them. ASH’s map of this programme is first and foremost a weapon in the fight against the propaganda war waged by the political parties whose housing policies are based on this programme, the London councils implementing it, the housing associations receiving public funds to profit from it, the public think tanks employed to justify it, the estate agents that produce the viability assessments that demand it, the builders, property developers and architectural practices getting rich from it, and the press that promotes the lies and silences the truth about it. That’s a lot to place on one map, so we decided to make it as big as we possibly could. This article is how we went about creating it.

Within a year Sid’s list had increased to 109 estates, and when he posted the latest update on the ASH Facebook page at the end of April 2017 I asked him if I could steal his format (he said ‘yes’) and add those estates I knew about that were not already on the list, bringing the total up to 130. As chance would have it, it was six weeks to another election – the big one this time; and on Monday 2 May I posted the new list on ASH’s social media pages with the announcement that we would be updating it every Monday leading up to the General Election. By ‘we’ I meant Sid, myself and L.G., whose knowledge of London’s estates, in my experience, is unequalled, and whose knowledge of whether one of them is threatened with regeneration is not taken from council websites but from visiting the estate, recognising the tell-tale signs (lack of maintenance, shut down community centres, evicted local businesses, closed garages, restricted parking, fenced-off playgrounds, threatened public gardens, and a sudden increase of estate agents, ethically-sourced coffee shops and artisanal bakeries in the area), and above all from talking to the residents. It was she who was mostly responsible for compiling the initial list. But once we had announced our intentions publically, numerous followers of ASH on both Facebook and Twitter began contributing their own knowledge about the threat to estates they lived on or near or otherwise knew about.

As a result, by the following Monday we’d identified 14 further estates threatened with regeneration by Labour councils, and the list was drawing virulent attacks on its veracity by numerous Labourites on social media. Leading the defence of the Labour Party’s complicity in estate demolition was Tom Copley, Labour’s Deputy Chair of the Housing Committee at the London Assembly, who over several days of vitriol accused ASH of ‘making stuff up’, of ‘lying’, of having ‘no credibility’, of deliberately ‘misrepresenting’, ‘misinforming’ and ‘misleading’ residents, of being ‘stupid’, of having a ‘burning hatred for Labour’, of being a ‘front for the ultra left’, of ‘not giving a damn about people living on estates’, of holding a ‘pathetic vendetta’ against the Labour Party, of ‘talking out of our backsides’, of ‘scaring’ people, of being ‘irresponsible’ and of ‘poisoning the complex debate about regeneration’. Finally, ASH was denounced as an ‘anti-Labour campaign, not a pro-estate one.’

We knew then that we were onto something. All these petulant attacks on us were gleefully re-tweeted by various members of Lambeth Labour council – whose plans to demolish six estates ASH has resisted over the past few years – including Florence Eshalomi, Lambeth and Southwark’s representative at the London Assembly; and Edward Davie, the Progress Chair of Lambeth’s Overview and Scrutiny Committee, who that same Monday had ignored residents’ questions when ratifying the Labour Cabinet’s decision to demolish Cressingham Gardens estate. And as always, Hackney’s Twitter-addicted Labour Mayor, Philip Glanville, couldn’t help joining in. The ostensible cause of their glee was that I had mistakenly added West Hendon estate to the list, which is of course in Conservative-run Barnet. This, in the judgement of Labour’s Tom Copley, was sufficient evidence to dismiss our list as ‘shonky’. When Tom ecstatically exposed another ‘mistake’ – that Imperial Wharf estate is in Conservative Westminster! – we gently reminded him that we were referring to the council estate in Harringey, not the luxury riverside development in Chelsea (though he’s clearly more familiar with the latter). I deleted West Hendon from the list and replaced it with the question: ‘Your estate next?’ Tom had nothing to say about the remaining 143 estates.

Undeterred by these childish insults and the accompanying smear campaign against ASH, we continued searching the less well-known estates in the outer boroughs of London – Merton, Hounslow, Waltham Forest, Barking & Dagenham and Redbridge – as well as returning to look at Tower Hamlets, Camden and Hammersmith & Fulham, and within two more weeks the list had increased to 155 estates. Organising a Lambeth hustings on estate regeneration the week before the General Election took up our remaining time, so this is where the list stayed until the poll booths opened on 8 June. A month later, following the decision by the Labour council to ratify the Haringey Development Vehicle that threatens, to our knowledge, 21 estates in the borough, the list was increased to 170 estates that are threatened by, currently undergoing, or which have recently undergone regeneration by London Labour councils.

2. The Map

That’s about where things stood when the Institute of Contemporary Arts offered ASH a residency over the week of 14-20 August. One of the many criticisms we had received from Labourites was that the list only included those estates threatened by Labour councils. ‘What about Tory boroughs?’ they angrily demanded. ‘We bet they’ve got just as many!’ It’s an idiotic argument – as if the actions of one party excused the other – and one typical of the rationalisations of Labour supporters; but we accepted the challenge readily, confident that Conservative councils don’t threaten anything like the number threatened by Labour councils. This is not only because there are more Labour-run boroughs in London (21 to 10) and generally speaking more estates in Labour boroughs (though this last factor is largely irrelevant considering just how many estates London contains – 150 identified on the Islington map alone – which means that any council, whether Conservative or Labour, has more than enough to demolish should they so choose), but because we know from our years of resisting and exposing it that estate regeneration in London is overwhelmingly a Labour programme led by Labour councils, who have pioneered the methods of implementation which Conservative councils merely observe and copy. Even we, however – with our ‘burning hatred’ for the Labour Party – would be surprised to discover just how numerically true this would prove to be when we decided to extend the list to include estate regeneration schemes in every London borough – whether Labour, Conservative or Liberal Democrat – and set about locating them on a map which we decided to create during the ASH residency at the ICA and display as part of the exhibition of our design alternatives to demolition over the weekend of 19-20 August.

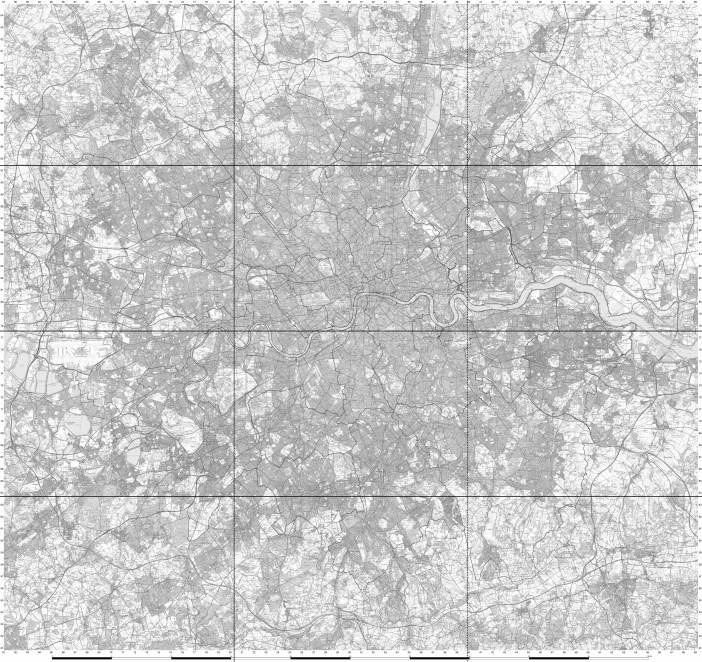

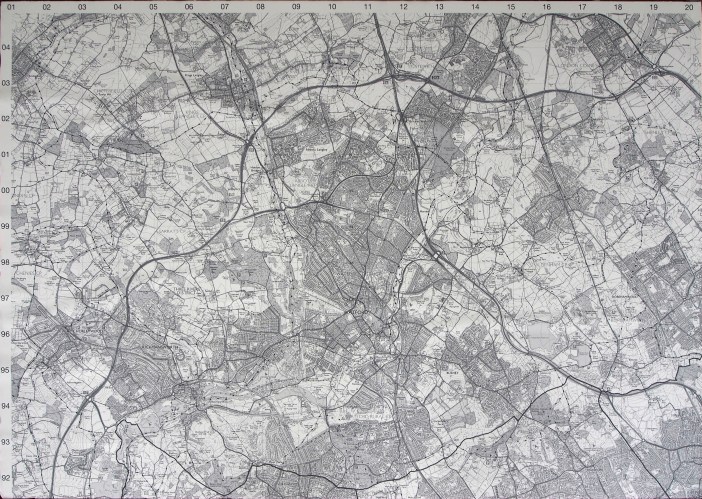

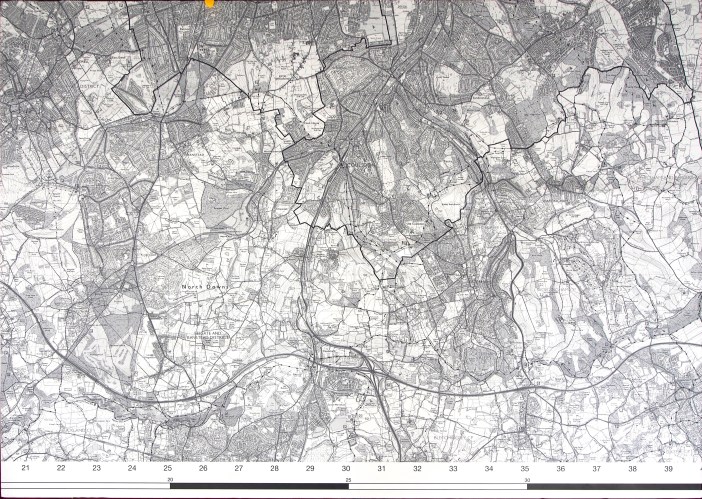

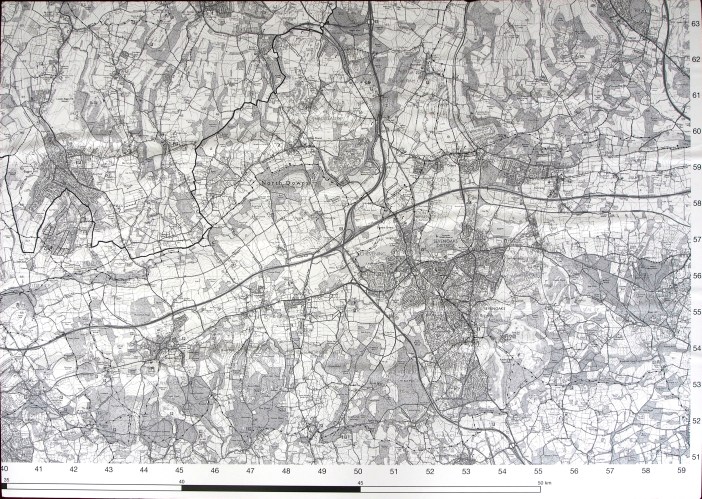

We announced our intentions on our social media networks and invited collaborators to help us, and at a preliminary meeting we were joined by Nicholas Fonty from JustMap. We had previously considered several typical maps, including, initially, the A-Z map of London, which proved – fortuitously, as it turned out – too expensive for our limited budget. What we did have, however, was lots of space, the ICA having generously granted us a week’s use of its Upper Galleries, whose walls from skirting to cornice measure about 4 metres. Since the map was to be made out of foam board into which we would be able to press brightly-coloured pins with extra-large heads, we decided to construct it out of twelve A0-size boards laid horizontally, three wide by four high, composing a map 3.56 metres across and 3.36 metres high at a scale of 1:16,000. When we considered how the coloured pin-heads would stand out against this enormous expanse, we realised that the map would work best if it was printed not in colour but in grey tones – which would, additionally, cost a fraction of the price. As always, necessity was proving the mother of invention. Rather than an A-Z map, therefore, whose purpose is identifying street names, we chose the most recent Ordinance Survey map of London. This meant that every block in London, including the footprint of the larger estates, could be identified. So up to date was the survey that some recently demolished estates – such as the Heygate in Southwark, into which we ceremoniously placed the first pin – were recorded as a white expanse of cleared land, while others, such as King’s Crescent estate in Hackney, showed the partial demolition of the central blocks preparatory to their redevelopment. The only problem this presented – the extent of which we would only realise when it came to inserting the pins – was identifying the exact location of the estates in a map without street names.

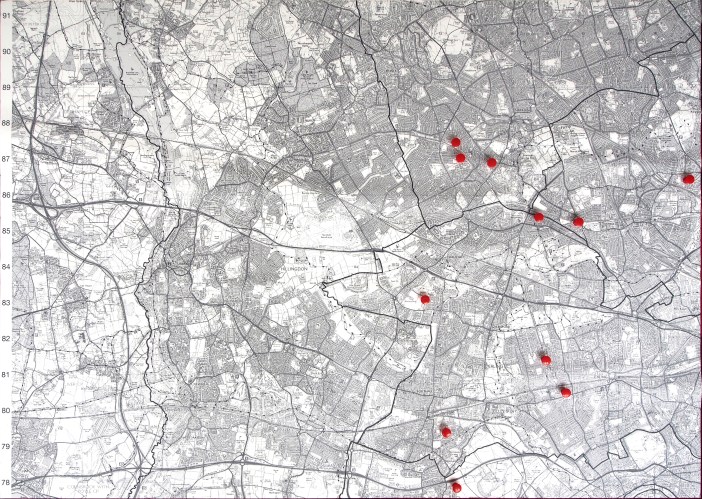

With the help of software provided by Nicholas, Geraldine printed out the twelve A0 Ordinance Survey map sheets, adding a grid reference around the edges that could be used to cross reference the list of estates we would exhibit alongside the map, and thereby enable viewers to identify the location of any given estate. We had anticipated spending the entire week creating this map, researching each estate, compiling what information about it we could find, and deciding on the best way to display it. As things turned out, however, our decision to open up the exhibition to the work of other collaborators with ASH meant we spent a large amount of the week simply putting the exhibition up. This began with me physically constructing the map itself – thickening the foam boards sufficiently for them to take the pins (the cost of thicker boards being beyond our budget) and mounting the maps on them – which took me the entire first day of our residency. The following day, while L.G. and I began sticking the red pins into the already identified estates in Labour-run boroughs, Nicholas and some other volunteers who had come to help, Harry Tuke, Barbara Brayshay of Living Maps, and Leslie Barson and Deirdre Dee Woods of Granville Kitchen, searched for estates in London’s Conservative-run boroughs.

After some discussion, we had previously agreed that the outer limits of the map would be the M25 motorway. Greater London has several definitions, but since we were mapping council-led regeneration schemes, and we did not yet know how far out they reached, it was necessary to include the extent of every London borough. Although many of these, particularly in the south-west, stop a long way short of the M25, in the case of Havering to the east the borough’s borders extend beyond the motorway and just off the edge of the map. We felt, though, that the strong line of the motorway worked to identify and define our frame of reference visually, and Nicholas had outlined every borough with a darker line, both to help identify its limits and to convey the terms of reference for the map as a whole.

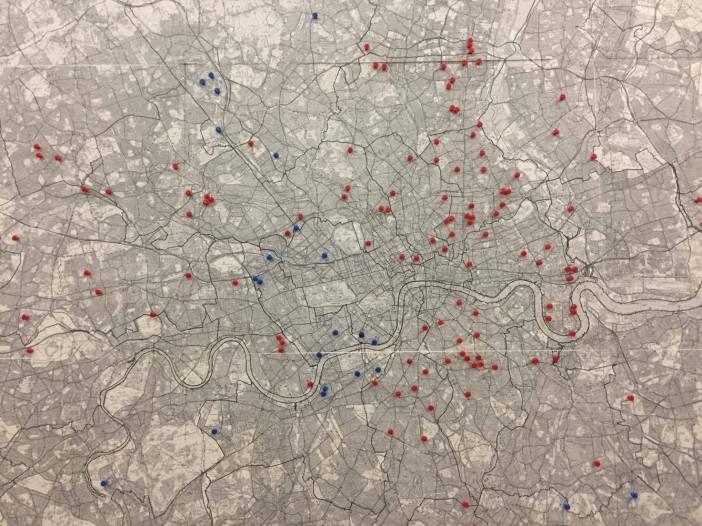

Given the political nature of the programme we were mapping, it had seemed obvious to us that each estate should be identified visually according to the political party of the London council implementing the regeneration scheme. Accordingly, we chose red pins for estates in the 21 Labour-run boroughs, blue pins for estates in the 10 Conservative-run boroughs, and yellow pins for the estates in the single Liberal Democrat-run borough of Sutton. As it turned out, this political identification of the councils implementing estate regeneration – which for us was the primary and obvious purpose of the map – had the most powerful and unexpected effect on viewers, who were shocked at just how many red pins there were, both comparatively and overall. That no one, as far as we’re aware, has done this before was not the least surprising aspect of this mapping project.

3. Definitions

The next thing we had to decide – although in practice there was little order to our decisions – was what qualified as an estate ‘regeneration’ and within what time frame. Estate regeneration can mean its refurbishment, as in the example of Lancaster West estate in North Kensington, which the Grenfell Tower fire has exposed as carrying its own threat to residents. What is less well known is that prior to the application of external cladding that circumvented the building’s fire stops, the carrying out of internal refurbishment that ran an exposed gas pipe down the escape staircase, and the conversion of the housing offices into nine new properties, Lancaster Green, the only local green space available for the residents of Grenfell Tower, was used for the development of the Kensington Aldridge Academy, and that the refurbishment that killed them was offered to residents as some sort of exchange for this loss of public land. Even when it seems otherwise, regeneration always comes at the expense of residents.

In order to serve its purpose, however, our map had to have a narrower focus. We could, for example, have included the public land being handed over to developers in sweetheart deals – such as Croydon Labour council, for instance, is doing with Queen’s Gardens in the Taberner House development. But we decided to restrict the definition of ‘regeneration’ to London estates under threat of, currently undergoing, or which have recently undergone 1) privatisation (typically in a stock transfer to a housing association, such as Hackney Labour council did with the Northwold estate, which is now facing partial demolition at the hands of the Guinness Partnership); 2) refurbishment (usually with the prior decanting of residents who – as happened with Balfron Tower in Tower Hamlets, which is now being marketed by Poplar Housing and Regeneration Community Association to Canary Wharf bankers – do not return); or 3) demolition (either partial or full); when all three forms of ‘regeneration’ result in the loss of homes for social rent and the corresponding social cleansing of all or part of the existing estate community.

As an example of the latter, which accounts for the overwhelming majority of so-called estate ‘regenerations’, we need look no further than Woodberry Down in Hackney, where 1,980 council homes are being demolished and replaced with 5,557 new properties, of which 3,292 will be for private sale and 2,265 will be so-called ‘affordable’ housing, the latter comprising 1,177 properties for shared ownership, with 1,088 flats promised for social rent. I emphasise the word ‘promised’, because Genesis housing association, which Hackney council has given the responsibility for delivering the affordable housing quota on the new development, has been outspoken about the lack of government funding for flats for social rent. And they’re right to do so. £4.1 billion of the £4.7 billion allocated for affordable housing by the Homes and Communities Agency between 2016 and 2021 is reserved for Help to Buy properties for shared ownership; and of the £2.17 billion allocated for affordable housing by the Greater London Authority in the same period, at least two-thirds of the funding is for Rent to Buy and shared ownership properties, which in the case of the Woodberry Down development start at £660,000 for a 2-bedroom apartment. In any case, of the 1,465 new units built in phase 1 of the redevelopment, a mere 110 flats are for social rent.

As for the time scale of such estate ‘regenerations’, it’s hard to identify exactly when the current programme began, both qualitatively in terms of the motivations, methods and political dimension of estate regeneration, and quantitatively in terms of the huge increase in the number of estates being regenerated and the equally huge number of homes for social rent being lost as a consequence.

But at one end of the time scale is the so-called ‘Five-Estate’ regeneration scheme in Peckham that demolished the North Peckham, Camden and Sumner estates and refurbished the Willowbrook and Gloucester Grove estates. Completed in 2004, the regeneration resulted in a reduction in housing across the five estates from 4,532 council homes to 3,694 mixed-tenure dwellings, a net loss of 838 homes. But the new developments also saw a tenure shift from 4,314 homes for council rent to 2,154 (a 50 per cent loss of 2,160 council-rented homes in a borough with 24,000 households on its housing waiting list), 915 housing association rentals and 625 market sale properties. In its reduction of the overall number of properties and the relatively large number of homes for social rent built on the new development, this regeneration scheme, which was undertaken in 1994 as a partnership between Southwark council and several property developers and housing associations, clearly belongs to the outer limits of the current estate regeneration programme, which invariably justifies the huge loss of homes for social rent with a dramatic increase in the number of properties for private sale on the new development. By contrast, in 2002 the Liberal Democrat/Conservative coalition council announced their decision to demolish the Heygate estate in Southwark, and by 2010 the newly re-elected Labour council had agreed a deal with property developers Lendlease to sell the land for £50 million (around one-fifteenth of its value), demolish 1,214 council homes and replace them with 2,535 properties, with the promise that 25 per cent will be ‘affordable’ and a mere 82 for social rent. Clearly by now something had changed in what was meant by estate ‘regeneration’.

At the other end of the time scale, in the Liberal Democrat-run borough of Sutton another five estates – Chaucer, Collingwood, Rosebery Gardens, Benhill and Sutton Court – are currently undergoing viability assessments – most probably conducted by Savills real estate firm, who are the go-to agents for London councils looking for the lowest number of homes for social rent on new developments (they produced the assessment for the Heygate) – in order to establish the options for their ‘regeneration’: refurbishment, stock transfer to a housing association, partial or full demolition and redevelopment. As with a hundred other designated ‘sink estates’, the money to carry out these assessments is being supplied by public funds as part of the government’s Estate Regeneration National Strategy.

As an example of why the first of these options – refurbishment – is unlikely to be the one chosen, in 2002 Lewisham Labour council proposed that the Excalibur estate in Catford be stock transferred to a housing association. In 2004 Savills dutifully produced a report saying that none of the existing homes were up to the Decent Homes Standard. The following year the council estimated the cost of refurbishment at £65,000 per home, and concluded that it would be too expensive to bring the homes up to this standard – what with all the Labour Government’s cuts and all. Finally, in 2010 the Homes and Communities Agency informed the poor cash-strapped council that it would not provide funding for a stock transfer, and Lewisham council promptly announced the full demolition and redevelopment of the estate as the only financially viable option. In 2011 the council granted planning permission to London & Quadrant housing association – which was no doubt involved from the start of the regeneration – to build 371 new properties on the cleared land, a more than 100 per cent increase in housing density; with 143 allocated for private sale, 35 for shared ownership, 15 for shared equity, and 178 designated as ‘affordable’. The Excalibur estate’s 178 council homes are currently being demolished phase by phase, the council tenants evicted and the 27 leaseholders offered a paltry £140,000 compensation for their demolished homes. Those who refused this offer have had their homes purchased by Compulsory Purchase Order issued by the Lewisham Mayor, Sir Steve Bullock – who just happens to be another co-author of the IPPR report City Villages. This is what ‘more homes, better communities’ means.

4. The Data

The next task facing us, of course, was finding this information for each estate. Those not familiar with estate regeneration may be surprised to learn that no record of the estates threatened by this programme is available: not from the Department for Communities and Local Government, not from the Greater London Authority, not from the London Housing Commission. And while the websites of local authorities will sometimes contain some information about the identity of the estates on their regeneration programme, it is always vague, misleading, incomplete, inaccurate or simply withheld altogether. In none of them is the number of homes for social rent lost to the scheme provided.

As an example of which, King’s Crescent estate in Hackney, following a partial demolition, is currently being redeveloped as the new Clissold Quarter. On the estate regeneration page for this scheme on Hackney council’s website it says that the regeneration of the estate will provide more than 760 homes, including for shared ownership and private sale. That’s all you get. A visit to the estate, however, will further reveal – on the hoardings advertising the development – that 376 of the new properties will be for private sale (‘to pay for the redevelopment’); 115 properties will be for shared ownership (‘for local people’); and that the regeneration will ‘increase’ the number of homes for social rent from 195 to 274 – a total of 79 new rented council flats. A further visit to the website of the architectural practice that designed the new development, Karakusevic Carson, will roughly confirm these figures, listing the regeneration as providing 765 dwellings, 490 new builds, and the refurbishment of 275 existing homes, with the tenure split between 50 per cent for market sale and 50 percent ‘affordable’. So, new homes, more homes, an increase in affordable homes, and the refurbishment of the existing homes. What’s not to like? This is how estate regeneration is presented by the people implementing it – by the architects, the developers, the councils, the mayor.

If you dig deeper, however, and look at the Greater London Authority’s planning report, very different figures emerge. King’s Crescent estate originally consisted of 632 council homes, which genuinely were ‘for local people’. But between 1999 and 2012 Hackney council demolished 357 of these, leaving the 275 ‘existing’ homes, of which 80 are owned by leaseholders. Far from being an ‘increase’, the 79 new flats for social rent are small compensation for the demolition of 357 council homes, of which 82 were owned by leaseholders. In total, the ‘regeneration’ of King’s Crescent estate has resulted in a loss of 196 homes for social rent. In their place, properties on the new development start at £480,000 for shared ownership of a 2-bedroom flat, £630,000 for private sale of the same, and go up to £1,313,000 for a 3-bedroom duplex. What has been universally described as an ‘exemplary’ regeneration is in fact a model of social cleansing whose truth has been concealed by the council, builders and architects, the Greater London Authority, the architectural press and the Royal Institute of British Architects, not to mention the line of dignitaries – from Hackney Mayor Philip Glanville and London Mayor Sadiq Khan to the Duke of Kent – who have traipsed through the building site, hard hats on their heads, soft muffs on their ears.

So how do we find this hidden information, how do we record it, and how do we convey it? When we were making the map for the exhibition at the ICA, these were largely questions for the future. Our task was to identify as many estate regenerations as we could that fell within the definition we had selected, and then locate them on the map. But we also compiled a list of these estates, grouped into boroughs and cross-referenced to the map’s grid lines. Finding this information, however, is difficult. Council websites are a starting point, however restricted the information made available to the public. The websites of architectural practices will offer much of the same – which is to say, very little. Property developers, housing associations and Special Purpose Vehicles set up by Labour councils, protected by the cloak of ‘commercial sensitivity’ even when demolishing public assets, have no obligation to provide any information. Where they exist, planning applications, either to the local or Greater London Authority, offer more, but these require considerable time to decipher. If you’re lucky, a journalist for the local rag will have dug up some basic information, though there is no guarantee of its accuracy. If you’re luckier, a local housing campaigner will have done the research for you; if every borough had the blogs of Southwark’s 35% Campaign, Southwark Notes or Municipal Dreams, our task would be very much easier. The online map produced by Concrete Action has been useful; and Our Tottenham has proved invaluable in tracing the full reach of the bulldozers that will precede the Haringey Development Vehicle, which the Labour council has done its best to hide from public scrutiny. ASH itself has produced case studies of more than a dozen estate regenerations in London, so we know what we’re talking about when we say how laborious and time-consuming the work is.

As for our national press – their investigative antennae pulsating with indifference – with the odd exception they habitually report little more than the press releases of councillors, developers, think tanks, the London Mayor and the Minister of State for Housing and Planning – hacks like the former Guardian journalist Dave Hill being the prime example. While the ‘case studies’ of estate regenerations in publications such as Urban Design London’s Estate Regeneration Sourcebook (2015), Savills’ Completing London’s Streets: How the regeneration and intensification of housing estates could increase London’s supply of homes and benefit residents (2016), HTA Design, Levitt Bernstein, Pollard Thomas Edwards, and PRP’s Altered Estates: How to reconcile competing interests in estate regeneration (2016), Karakusevic Carson’s Social Housing: Definitions & Design Exemplars (2017), London First’s Estate Regeneration: More and better homes for London (2017); the Labour Party’s Local Housing Innovations: The Best of Labour in Power (2016), the Conservative Government’s Estate Regeneration National Strategy (2016), or the Greater London Authority’s Homes for Londoners: Draft Good Practice Guide to Estate Regeneration (2016) – to name just some of the titles championing the benefits of the estate regeneration programme – uniformly fail to provide the figures on how many homes for social rent were lost to the regeneration schemes they claim to study, how much public land was privatised by the redevelopment, and how many former residents were socially cleansed from the estate as a result – everything, in other words, that would allow the reader to make a judgement about whether these estate regenerations are solving the housing crisis – as they claim to be – or exacerbating it.

And academics? I said before that the fact no one has previously mapped the political party of the councils implementing London’s estate regeneration programme wasn’t the least surprising aspect of this project. But even given the collusion of such apologists for social cleansing as the London School of Economics – whose report on Kidbrooke Village in Greenwich omitted to say that the 4,398 properties in the new development are being built on the ruins of 1,906 council homes and the social cleansing of 5,277 council tenants from the demolished Ferrier estate – what we find most incredible, if not exactly surprising, is that no salaried investigator, grant-funded PhD student, tenured academic, Research Councils UK researcher or Greater London Authority employee has undertaken this task, and that it has been left to ASH, an unfunded organisation of voluntary workers, to research the data on estate regeneration and create this map. In truth, it’s not surprising at all, but we’ll come to that later. The problem we face is how to overcome the active suppression and withholding of information about London’s estate regeneration programme.

5. Collaborating

Which is where you come in, and the purpose for writing this article. By far the most reliable, accurate and up-to-date source of information on an estate regeneration comes from the campaigners fighting to resist it. By the time we put the last map panels up on the gallery wall late on Friday evening we had stuck appropriately coloured pins into 195 estates in the 21 Labour-run London boroughs; 37 estates in the 10 Conservative-run boroughs; and 5 estates in the single Liberal Democrat-run borough: a total of 237 London estates under threat of, currently undergoing, or which have recently undergone privatisation, demolition or social cleansing. Given the time restraints of the exhibition, some of these estates will have been inaccurately identified for one reason or another; some other estates are yet to be identified; and many more will join them over the ensuing months and years. There is no definitive version of this map for the simple reason that it can only ever be accurate at one given moment, while estate regeneration is an ongoing programme that is set to increase in numbers and reach. Our own project, because of this, is equally ongoing.

We want to take this opportunity, therefore, to appeal to the public – residents, housing campaigners, council employees, architectural workers, even journalists and academics – to send us information about any estate regeneration scheme they can identify and, where possible, provide some of the data for it. As an example of what we’re looking for, the list of estates we displayed next to the map at the exhibition contained the following information: a) The borough in which the estate is located; b) The political party of the current council; c) The name of the estate; d) The grid reference to the map; e) The status of the regeneration (undergoing viability assessment, currently threatened, awaiting planning permission, on site, or completed); f) The form of its regeneration (stock transfer to a housing association, refurbishment, partial demolition, full demolition); g) The number of existing homes; h) The number of homes that will be or have already been demolished; i) The net loss of homes for social rent; and j) The number of new properties being proposed or already built.

This is the basic data we’re after. In addition, where possible we’d also like 1) The street address and postcode of the estate, which particularly helps in locating the smaller estates; 2) The completion year for the construction of the estate; 3) The identification of the tenure of the homes now or at the moment of their demolition (council rent, housing association rent, assured shorthold tenancy, property guardianship, leasehold, freehold, or vacant); 4) The number of existing homes refurbished; 5) The tenure split for the proposed or newly built properties (private sale, private rent, shared ownership, affordable rent, council rent, or social rent); 6) The name of the existing or previous social landlord (local authority or housing association); 7) The name of the development partner (housing association, property developer or builder); 8) The name of the architectural practice responsible for designing the new development; 9) The sale price of the land; 10) The value of the redevelopment contract; 11) The amount of public money granted for the regeneration; 12) The public body issuing it (council, GLA, HCA, DCLG); and 13) The new name – where a new one has been coined (Oval Quarter for Myatts Field North estate, Kidbrooke Village for the Ferrier estate, Orchard Village for the Mardyke estate) – for the new development. It would also be useful to have the link to the primary source of this information, whether a planning application, article or blog post.

Finally, our intention is to make this data as widely available as possible, and to this end we intend to make an online, interactive version of the ASH map. At present, however, we do not have the technical skills, financial resources or the free time to do so; so we also invite people with all three to collaborate with us on producing such a version. We will be looking into crowd-funding for help with the finances required to complete the research for and production of this online map; but if anyone is in receipt of funding or would like to award us the grants that have so far eluded our applications to various trusts, it would certainly be of help to our work. If you are able and would like to help us assemble this data, please send us as much information as you can by e-mail, if possible grouped into the alphabetical and numerical categories we’ve provided, at info@architectsforsocialhousing.co.uk.

6. Uses and Abuses

It was only on the Friday evening before the ASH exhibition opened, when we had lifted the last panels into place and saw the archipelago of red, blue and yellow pins dotted across the expanse of Greater London, each one an indictment of greed, the power of money to overcome human rights, and the collusion of our democratically elected public representatives in the social cleansing of Inner London, that we were struck by the obvious. No one wants to see this map: not, certainly, the London councils responsible for implementing the estate regeneration programme; not the Greater London Authority and Labour Mayor whose every statement and publication about regeneration this map refutes; not the builders and property developers getting rich on the redevelopment of the cleared land; not the housing associations to whom billions of pounds of public housing and government funding is being transferred to build properties for private sale; not the real estate firms producing the viability assessments that justify the demolition of tens of thousands of council homes in the middle of a housing crisis; not the so-called ‘independent’ think tanks being paid by political parties, builders and housing associations to justify the eviction from Inner London of hundreds of thousands of residents; not the academics who produce reports commissioned by developers dutifully recommending developments like Kidbrooke Village as the model for London’s future housing; not the architectural practices selling this vision of London to the residents their designs will banish from it; not the architectural press, not one of whose journalists turned up to the opening or reported on the ASH exhibition; not the mainstream press which did likewise, and which continues to refuse to publish the truth about estate regeneration, even in the wake of the Grenfell Tower fire; not, certainly, the so-called housing movement, 99 per cent of which is made up of supporters of the Labour Party; not the so-called ‘grass-roots’ fronts for the Labour Party, whether Axe the Housing Act, Defend Council Housing, the Radical Housing Network, the Socialist Workers Party, the People’s Assembly, Momentum, or all the other groups that claim to oppose estate demolition while suppressing the role of the Labour Party in implementing it; not the unions who unreservedly support and finance the Labour Party no matter what consequences its policies and practices have for working class homes; not the Labour Party itself – neither the MPs who unceasingly complain about Tory cuts while doing nothing to oppose the Labour councils demolishing the homes of their constituents, nor the Labour Party Leader, who in the two years of his leadership has steadfastly refused to make a single comment about the programme his party is implementing; not the constantly changing housing ministers – Government or Shadow, Tory, Labour or Liberal Democrat – all of whose policies, published in the election manifestos, are based on the continuation and expansion of the estate demolition programme.

For what these people will see if they look at the ASH map is this: that London’s estate regeneration programme has nothing to do with freeing up land for the new housing that Londoners need; that it is designed above all to demolish the housing estates in Inner London; that its primary purpose is to clear the enormously valuable land on which these estates are built for redevelopment as high value property for capital investment, property speculation and home ownership; that it has already demolished thousands of council homes, privatised thousands more, currently threatens tens of thousands, and will, if unchecked, demolish the homes of hundreds of thousands of Londoners, who as a consequence will be forcibly relocated either to the outer suburbs of London or outside the capital altogether and into an unregulated private rental market; and, finally, that this is a cross-party programme to which every London council has subscribed, whose methods and procedures have been pioneered and are overwhelmingly being implemented by the Labour councils that are responsible for over 80 percent of London’s estate regenerations, but on which the housing policies of all the political parties holding power in London’s councils are founded.

So who is this map for? Well, for a start, it’s not for academics. Estate regeneration isn’t the topic of a conference debate; it isn’t archive material for a peer-reviewed book; it isn’t a contribution to a university department’s research rating; and it isn’t the subject of government grant-sponsored research into ‘gentrification’: it’s a struggle for survival. Presenting the government and municipal bodies that are implementing the estate regeneration programme with government-funded studies into the results of what they are doing won’t tell them anything they don’t already know. They designed and adapted the programme precisely in order to achieve these ends, and the supposition that they are not aware of what those are is a naive and dangerous fallacy that only serves to exempt them from responsibility.

Nor is the map necessarily for the residents whose homes are threatened, and who, understandably, are focused on the struggle to save their own estate from the bulldozers. Behind the heroic rhetoric in which they are sometimes wrapped by campaigners (myself included) eager to politicise their struggle, residents of council estates are no different from other tenants and leaseholders in London, and in general have a limited interest in opposing the economic and political structures driving estate regeneration. That’s not surprising, since their opposition to it has been forced upon them by necessity, not chosen out of political conviction.

But in truth this map is not ‘for’ anyone. Rather, its only practical use, as far as I can see, would be similar to the way that the original list of 40 estates was used by Sid Skill: as a propaganda weapon in the class war being waged through housing. By this I don’t mean some variation on the popular and entirely ineffective tactic of pointing to something like this map and shouting ‘shame on you!’ at a councillor or developer – which, rather like academic studies intended for property developers and housing associations, assumes that such people don’t already know exactly what they’re doing, and do have a sense of shame about doing it. No, the only use I can see for this map that ASH has already spent so much time researching and creating is to inform people who are not already aware of the existence, extent and effects of London’s estate regeneration programme, and who by being made aware will – without immediately being dragged into the black hole of the Labour Party and its affiliates – come up with a way – which we ourselves have so far been unable to find – to stop it.

For the truth – to which this map is the testimony and warning – is that at present there is no way to halt the spread of the estate regeneration programme across London and, in time, the rest of England. Knowledge may be power, but only when it informs and is aligned to political action, which should not be confused with the electoral campaign of a parliamentary party, the research profile of academics, or what increasingly resemble the social gatherings of activists. After two-and-a-half years of campaigning it’s still unclear to us who this new group of people may be. We’ve met a few of them along the way but nowhere near enough to constitute anything more than a commentary on what’s happening. We offer this map as a rallying point.

Simon Elmer & Geraldine Dening

Architects for Social Housing

Installation photographs by L.G.

Architects for Social Housing is a Community Interest Company (no. 10383452). Although we do occasionally receive minimal fees for our design work, the majority of what we do is unpaid and we have no source of public funding. If you would like to support our work financially, please make a donation through PayPal:

Wow!

LikeLike

Hello there, is this a good address to make contact with ASH? I am an ex- council housing architect, recently retired from teaching Housing design and development at Sheffield Hallam University. I am also a recently joined Labour Party activist, living close to the well-known Gleadless Valley estate in Sheffield. The estate has recently been earmarked for a Regeneration Programme, and we all know what that means! £505k has been allocated for , we believe, although not confirmed yet,consultation. I am very keen to get residents involved in this, and particularly keen to get ASH on board as the consultants, as I am entirely in agreement with your politics and think your work and activism is excellent, exactly what I have been doing during my work as an architect. Let me know if you have received this email, and whether ASH is interested. all the best, Jenny Fortune RIBA 3, MA in Housing Planning and Development

On 10 September 2017 at 13:16, architectsforsocialhousing wrote:

> architectsocialhousing posted: ” 1. The List As I turned to camera and > explained why I had just pursued first Sadiq Khan and then Jeremy Corbyn in > opposite directions down the same Islington street, asking them questions > they both resolutely refused to answer about their support for the” >

LikeLike

Hello Jenny, Geraldine Dening will be speaking about ASH in Sheffield on Thursday, 19 October, as part of a programme organised by Dr Tatjana Schneider from the School of Architecture at the University of Sheffield. It hasn’t been confirmed yet, but the venue will most probably be the Foodhall. https://www.facebook.com/foodhallproject/ It might be a good opportunity for you to go along and see the alternative designs we’ve done and have a chat with Geraldine. You can contact us further at: info@architectsforsocialhousing.co.uk. Best wishes.

LikeLike

I am interested in your program, having worked in social housing in London for 20 years before emigrating 30 years ago. Are you still active as a group ? Do you where it is possible to obtain a readable copy of the map of Islington housing estates shown in your website?

LikeLike