A PDF file of this report is available here: The Truth about Grenfell Tower

On Thursday, 22 June, 2017, in response to the Grenfell Tower fire the previous week, Architects for Social Housing held an open meeting in the Residents Centre of Cotton Gardens estate in Lambeth. Around 80 people turned up and contributed to the discussion – residents, housing campaigners, journalists, lawyers, academics, engineers and architects. Below is an edited film of the meeting made for us by Line Nikita Woolfe, with the assistance of Luc Beloix on camera and additional footage by Dan Davies, and is produced by her company Woolfe Vision. The presentations we gave that evening are the basis of this report, to which we have added our subsequent research as well as that collated from the numerous articles on the Grenfell Tower fire published in the press and elsewhere, to which we have attached the weblinks, with the original documents included whenever they are available.

Architects for Social Housing is a Community Interest Company (no. 10383452). Although we do occasionally receive minimal fees for our design work, the majority of what we do is unpaid and we have no source of public funding. If you would like to support our work, you can make a donation through PayPal:

Introduction

On the Saturday after the Grenfell Tower fire we ran into a member of the Tenants and Residents Association for Cotton Gardens estate, which includes three 20-storey blocks, and she told us that she had received over 50 calls from residents worried about the safety of their homes. We decided, therefore, to call a meeting on the estate to try and answer their questions and those of residents from other estates alarmed by the reports in the media about the safety of council estate tower blocks, and give them any advice we can on how they can put pressure on their landlords to improve that safety. To do so, we started looking at the causes of the Grenfell Tower fire – not only the technical causes but also the management structures and political decisions that led to them. In addition, we ourselves have been alarmed by the increasingly loud and widespread narrative being spread in the media that council estates are inherently unsafe and that the proper response to this disaster is to demolish all council tower blocks.

As any resident who has been consulted by their local council on the ‘regeneration’ of their estate knows, their responses to seemingly innocuous questions are similarly used to justify the demolition of their homes. As an example of which, one of the questions put to residents of Central Hill estate by Lambeth council at the beginning of their consultation was ‘would you like a new kitchen?’ Two-and-a-half-years later the same council used the answers to these consultations to justify the demolition of the entire estate. In the same way, opinions about living in council tower blocks voiced in the wake of the Grenfell Tower fire are not made in a political vacuum. It is entirely understandable that a resident pulled from the hell of the Grenfell Tower fire and shoved in front of a camera crew should call for the demolition of similar tower blocks; it is something very different for a journalist who has never lived on an estate to do the same in a national paper, as it is for a politician who has promoted London’s programme of estate demolition to describe tower blocks as ‘criminally unsafe’ on a news programme watched by millions. This report makes no claim to be the truth about the Grenfell Tower fire, but it is a contribution to the attempt to find it, which also means exposing and refuting the lies being spread about its causes. In trying to find that truth, we should be aware of the difference between voicing our personal opinions and formulating conclusions based on what we know.

We wanted to use this meeting, therefore, to counter the misperceptions and misinformation being propagated in the media, not only about the Grenfell Tower fire but about the council estate it belongs to, and to begin to organise opposition to the use of this disaster and the lives it has claimed to further promote the already widespread programme of estate regeneration that threatens the homes of hundreds of thousands of Londoners. In order to cover these issues in what turned out to be two-and-a-half hours, the meeting was divided into four sections, each with a clear objective: 1) to share what we know collectively about the technical causes of the Grenfell Tower fire; 2) to expose the management structures and political decisions that allowed these technical conditions to be in place; 3) to advise residents of council tower blocks on the safety or otherwise of their homes, and what changes need to happen in order to stop such a disaster ever happening again; and 4) to organise opposition to the use of the Grenfell Tower fire to promote London’s programme of estate demolition. In writing up our presentations, however, we have expanded this report into six parts:

1. Technical Causes of the Grenfell Tower Fire

Grenfell Tower Building Regulations

Grenfell Tower Cladding

2. Management Decisions responsible for the Grenfell Tower Fire

Grenfell Tower Management

Grenfell Tower Refurbishment

Grenfell Tower Responsibilities

3. Political Context for the Grenfell Tower Fire

Grenfell Tower Regeneration

Grenfell Tower Appearance

Grenfell Tower Profits

4. The Fire Safety of Council Tower Blocks

Grenfell Tower Precedents

Grenfell Tower Warnings

Grenfell Tower Residents

Grenfell Tower Deregulation

5. The Programme of Estate Regeneration

Grenfell Tower Opportunism

Grenfell Tower Politics

Grenfell Tower Community

6. Accountability for the Grenfell Tower Fire

Grenfell Tower Inquiry

Grenfell Tower Inquest

Grenfell Tower Legacy

Part 1. Technical Causes of the Grenfell Tower Fire

ASH visited Grenfell Tower on the Thursday after the fire, which started shortly before 1am on Tuesday, 14 June. The neighbouring Silchester estate is under threat of demolition by Kensington and Chelsea council, and we know residents in the campaign who live on Silchester Road, 100 metres north-west of Grenfell Tower. We were therefore able to pass the police cordon and get a close look at the burned-out building. The residents showed us photos of the tower that they had taken from their back garden, and told us that the fire, which began in a fridge-freezer of a flat on the north-east corner of the fourth floor, spread up the corner cladding in a column of flame that reached the roof, twenty floors above, within 15 minutes. It then moved laterally across the cladding in a diagonal line, moving around both sides of the building, meeting at the south-east corner, and eventually encasing the entire tower in flames. Footage confirming this account was taken by fire-fighters approaching the scene, and the question they ask each other several times in disbelief is: ‘How is that possible?’

Grenfell Tower Building Regulations

A building is the sum of its parts, and works holistically. Any changes to its constituent components will therefore alter the fire strategies that are intrinsic to the design of the building. All works to buildings, whether refurbishment or new build, need to pass the 2010 Building Regulations. These regulations are updated regularly, and particularly in response to incidences of fire, which are contained in Approved Document B, which was produced in 2006 and amended in 2010 and 2013. There are several ways that designs get Building Regulations approval from local authorities. 1) The drawings can be sent to the local authority and be approved by their Building Control department as part of a Full Plans application, which generally takes around 8 weeks. 2) Alternatively, it is also possible to submit a Building Notice to the local authority and start construction on site 48 hours after the submission and potentially long before the designs are completed. The difference is, the Full Plans application receives design approval from the council before construction starts, whereas the Building Notice receives a Completion Certificate once the works are completed. In both routes to approval, the building works are inspected throughout construction by an in-house inspector from the council’s Building Control department. According to the Planning Portal, with a Building Notice:

‘Plans are not required with this process so it’s quicker and less detailed than the full plans application. It is designed to enable some types of building work to get under way quickly; although it is perhaps best suited to small work.’

There are also works for which a Building Notice is excluded, including building work which is subject to section 1 of the Fire Precautions Act 1971, for which a certificate issued under this Act by the fire authority is compulsory. Under a Building Notice, the local authority is simply informed about the works and monitors it as it progresses to ensure the work complies with Building Regulations.

Building Regulations are updated in order to accommodate the use of new technologies, so alterations or additions to existing buildings that, like Grenfell Tower, have been standing for 40 years must first ensure that any work done to that building – whether remedial, cladding or refurbishment – works in conjunction with that building and doesn’t compromise the building’s existing integrity. This means the fire safety and risk measures need to be re-analysed and the new conditions under which they function taken into account. In the case of Grenfell Tower, the new works appear to have compromised the existing fire safety of the building. In an interview about the fire, Arnold Tarling, an Associate Director of Hindwoods Chartered Surveyors and a member of the Association for Specialist Fire Protection who has also advised the All-Party Parliamentary Fire Safety and Rescue Group, gave a detailed account of what he thought had happened in the Grenfell Tower fire (illustrated in this BBC diagram below) and why the Building Regulations didn’t prevent it happening:

‘There was an initial source of fire. That cause is entirely irrelevant to what happened later. What happened is the fire got out of a flat, maybe from an open window or through a broken window from the heat. And then it started heating the panelling and the insulation above [yellow in the diagram below]. That then set a chain reaction, in which the panel started to burn.

‘The panels, being aluminium, melt at 600 degrees or thereabouts. But the Fire Brigade cannot put out any of the fires behind these panels, because there’s metal there. You also have a wind tunnel effect sucking the flames up between the insulation and the external cladding, melting the solid polyethylene above, and continuing the fire right up the height of the building.

‘The cladding system is combined polyaluminum sheets with a filler of polyethylene. And that is what has caused the problems, because the polyethylene melts at a very low temperature and it catches fire. It is basically like a candle which is sandwiched between two sheets of metal.

‘The building regulations we have in this country are not fit for purpose with regards to this form of cladding. All that you require to meet the standards is that the outside surface shouldn’t allow the spread of flames. What is going on behind the metal or the other surface is entirely irrelevant to Building Regulations.’

This account of the combustion of the cladding panels and insulation was corroborated by Deputy Superintendent Fiona McCormack, who is overseeing the police investigation into the fire. She confirmed that preliminary tests of the insulation samples collected from Grenfell Tower showed they combusted soon after the tests started, and that the cladding panels also failed the safety tests – with the insulation proving, she said, ‘more flammable than the cladding.’

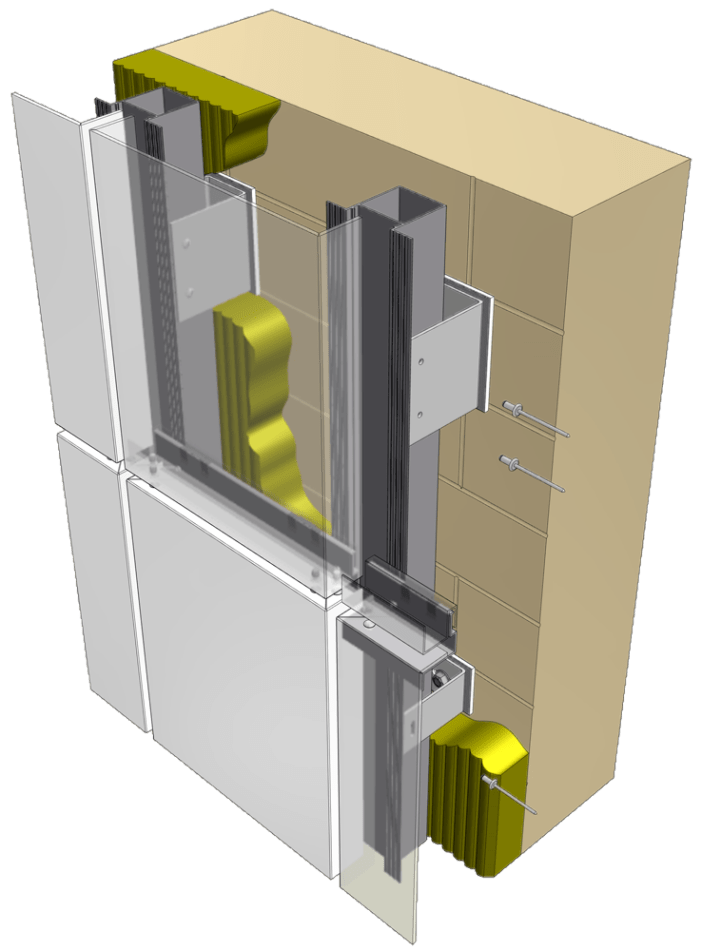

Close-up photographs of Grenfell Tower after the fire, when both the insulation and the panelling had mostly burnt away, show some of the metal fixings for this cladding system, as seen in the detailed plan below from the manufacturers’, Arconic. In practice, moisture penetration at these points can corrode steel-reinforced concrete structures and considerably shorten the life of the building; and in such instances cladding not only does not fix internal issues, such as the thermal performance of the building, but actually makes them worse, while also creating new problems.

The most lethal of the new problems created by the attachment of cladding to Grenfell Tower was that the panels appear to have circumvented the firestops that were part of the fire safety measures of the original design of the tower. As in all tower blocks, these firestops sub-divided the building into discrete compartments separated by fire-resistant walls, floors and doors which are designed to slow the spread of fire from one compartment to another through their resistance to collapse, the transfer of heat and penetration of fire. Under Approved Document B (fire safety) of Building Regulations 2010 it states:

‘If a fire-separating element is to be effective, then every joint, or imperfection of fit, or opening to allow services to pass through the element, should be adequately protected by sealing or fire-stopping so that the fire resistance of the element is not impaired.’

In 2015 the London Fire Brigade was so concerned about the failures of councils to take responsibility for the risks consequent upon refurbished high-rise blocks that it issued all 33 local authorities with an audit tool to aid them in conducting a risk assessment. According to the Observer, only 2 of London’s 33 councils – Enfield and Kingston upon Thames – confirmed they had applied the audit in full. Part of the London Fire Brigade’s campaign Know the Plan, which was launched in response to their fears that competition to reduce costs had led to the refurbishment of estates being signed off by council’s without adequate scrutiny, the audit states:

‘London Fire Brigade is concerned about the arrangements in place for protecting the fire safety precautions of a building, especially if it has been refurbished or if any modification or maintenance projects have been carried out. In the Brigade’s experience, buildings can and do become compromised in fire safety terms by works carried out. These works can be high or poor quality; they might be carried out for very desirable reasons; but sometimes many different types of works can unintentionally damage the fire safety arrangements of a building.’

The question we need to ask, therefore, is how the refurbishment of Grenfell Tower compromised the effectiveness of the firestops to the degree it did, to the extent that fire doors and walls that should have contained the initial fire in the flat in which it started for at least an hour instead allowed the fire to spread up to the roof within 15 minutes and then engulf the entire building within the next 2 hours. A previous fire in Grenfell Tower that started in a lift lobby in April 2010, long before the refurbishment, was contained within the designed fire compartments without any resulting injuries, let alone loss of life. So what was it that made this fire, seven years later, so deadly?

Grenfell Tower Cladding

In 2016, as part of the refurbishment of the Lancaster West estate to which it belongs, Grenfell Tower was fitted with external cladding. This consisted of three layers:

1. A 150mm-thick layer of Celotex RS5000 thermal insulation (yellow in the diagram above) fixed onto the precast concrete panels (brown in the diagram) and the reinforced concrete frame. We found charred remains of this insulation material lying everywhere around the base of Grenfell Tower, together with the thin foil sheets that covered it. The Architects’ Journal has indicated that in the designs for the cladding this insulation layer had a timber backing. Celotex, which is made from polyisocyanurate (PIR), has a Class 0 fire performance rating, the highest rating a material can get in the Building Regulations. However, as Arnold Tarling said, this rating indicates surface spread, not resistance, and its Health and Safety Datasheet notes:

‘The products will burn if exposed to a fire of sufficient heat and intensity. As with all organic materials, toxic gases will be released with combustion. Fire fighters should attack the fire according to the combustible materials present, and use breathing apparatus.’

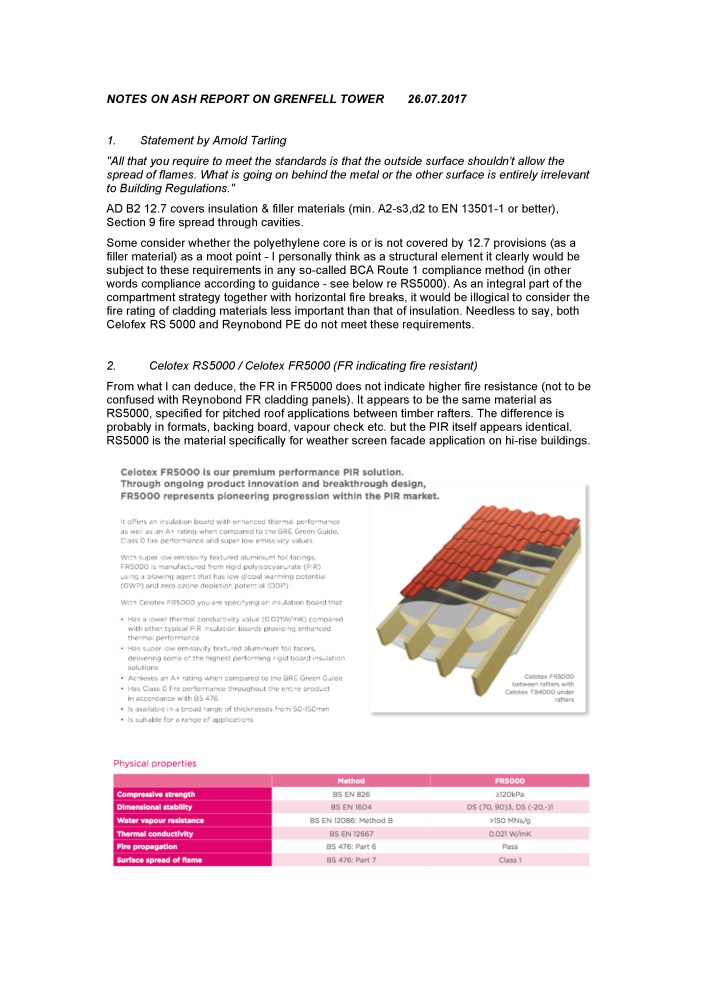

Celotex is manufactured by Saint Gobain UK, and the Times has revealed that the company’s technical director, Mark Allen, sits on the Building Regulations Advisory Committee, a non-departmental public body that advises Sajid Javid, the Communities and Local Government Secretary, on making Building Regulations and setting standards for the design and construction of buildings. Following the fire Saint Gobain confirmed that they had supplied Celotex RS5000 for use at Grenfell Tower, and not Celotex FR5000 (FR indicating fire resistant) as had been specified in the August 2012 Sustainability and Energy Statement that was published as part of the Planning Application by the engineering consultants for the refurbishment, Max Fordham. Saint Gobain has since announced they will be discontinuing the supply of Celotex RS5000 ‘for use in rainscreen cladding systems in buildings over 18 metres tall.’

2. A cavity or gap of 50mm between the first layer of thermal insulation and the cladding panels in order to allow any build up of moisture to evaporate.

3. An outer layer of cladding (grey in the diagram) consisting, on the ground floor columns, of BCM glass reinforced concrete (GRC), then from the mezzanine to the roof of Reynobond aluminium composite material (ACM) rainscreen cassette panels. This is a sandwich of two coil-coated aluminum sheets, each 0.5mm thick, fusion bonded to a 6mm-thick core, the purpose of which is to give strength and rigidity to the panel. A company director for Omnis Exteriors, the company that supplied the Reynobond panels, has told the Guardian that the companies that refurbished Grenfell Tower asked them to supply Reynobond PE cladding, which is £2 cheaper per square metre than the alternative Reynobond FR, which stands for ‘fire retardant’, and which contains a mineral core. The cheaper Reynobond PE contains a polyethylene core, which burns slowly, even after being removed from a flame.

The Principal Designer for the refurbishment of Grenfell Tower was Studio E Architects, which has subsequently removed all information from its webpage on the refurbishment. Before they did so, however, an architect with considerable experience of fire safety took this screen grab of a photograph (above) of the cladding and sent it to ASH. What it clearly shows is that in addition to the 50mm gap between the rain-screen panelling and the insulation, there is a considerably larger void between that and the ten concrete rotated pillars that run up the building, not only creating a series of full-height vertical voids for smoke and flames, but completely bypassing the horizontal fire stops at each floor, thereby rendering them useless. This is confirmed by the plan detail in Studio E’s drawings for the cladding (below).

At the four corners of the tower the cladding formed large boxes around the concrete pillars, creating even larger cavities for the heated air, which would account for the fire moving up from the fourth to the twenty-fourth floor in just fifteen minutes. And as the architect who sent us the screen grab observed, whatever cavity stops there were between the cladding and the concrete wall were only as secure as what they were fixed to – which, given the rapidity with which the fire spread up the cladding, doesn’t appear to have been much. On the contrary, it appears that the fire stops at each floor of the tower stopped short at the insulation, and didn’t extend into the plane of the rainscreen panels (as illustrated in the Guardian diagram below).

A further effect of the cladding was that its installation appears to have moved the position of the windows in the tower block outwards, creating a gap between the window frame and the concrete wall through which smoke could pass. In a detailed blog post by technical designer and housing campaigner Ian Abley titled ‘Mind the Planning Approved Interface Gap at Grenfell Tower’, a photograph (below) reproduced from a Grenfell Tower Regeneration Newsletter dated August 2014 shows cladding samples in situ. Again, the extent of the void between the cladding and the concrete walls is revealed, but also how far back the existing windows are set as a result.

The concomitant re-positioning of the windows was proposed in changes to the design made by Studio E Architects and planning consultants IBI Group and accepted by Kensington and Chelsea council planners in January 2015 (application NMA/14/08597). The Studio E drawing (below) shows the existing window position in black, with the proposed window position indicated in red. This meant pulling the windows forward of the original concrete structure. It was proposed that the existing window frame could be retained under the proposed linings, and that the new window could be located within the rainscreen system, attached to the support of the concrete structure on brackets. This created a gap between the new window frame and the existing concrete structure, shown to be partially filled with different insulation to that in the rainscreen panelling.

As Ian Abley warns, this is only a drawing at the planning stage of the refurbishment process, and therefore a snapshot in time; but the planned separation of the windows from the concrete meant that this gap would have been technically critical for the spread of the fire from the initial source in the flat to the cladding:

‘The several materials and products within the interface gap became the only construction stopping a fire inside a flat from reaching the insulated cavity, inside the rainscreen build up, and then the cladding on the outside of the building. If fire got inside the cavity through the interface gap between window and concrete only non-combustible cladding and insulation would resist ignition.

‘If a fire happened in a flat compartment, it is likely too that the window glass would shatter and fall away. Fire could flare through the opening and scorch the cladding externally. The cladding face might resist some spread of flame. But if exposed for long enough only a non-combustible cladding would resist ignition. A flat fire happened.

‘Once inside the rainscreen, having bypassed the window, the fire could spread via variously combustible products. Fire would bypass any cavity fire barriers installed. It would spread upwards and across, from window to window opening. Fire in the cladding and involving the insulation might be able to break back into flats at every level through the same interface gap around the window frames’

Finally, in addition to the cladding, there is also the question of how the fire safety of Grenfell Tower was compromised by the maintenance of its interior – something residents complained about since 2013, long before its external refurbishment in 2016, and to which we will return in Part 4 of this report. This maintenance work – or lack of it – undoubtedly contributed to the spread of the fire internally and the difficulty residents had in escaping from the building; but from our analysis of how the fire spread we believe that it was not the cause of the rapidity with which it engulfed the building, making it impossible for the London Fire Brigade to fight it effectively. Rather, the technical conditions that made the fire in Grenfell Tower so deadly to its inhabitants, consuming the building with a speed and ferocity which the approaching fire fighters didn’t believe was possible, was a direct result of its refurbishment, which not only circumvented the firestops at each floor level, but in addition created a chimney effect between the cladding and the insulation that swept the smoke up the building. Footage of the fire (below) taken by witnesses shows that this chimney effect was strongest in the column cladding running up the building, where the gap between the insulation and the concrete was at its largest. This chimney effect heated up the panelling before setting it on fire and ignited the flammable insulation, which in turn released the hydrogen cyanide that would have overcome most of the inhabitants before the flames reached them. In an interview with the Architect’s Newspaper, a firefighter from the London Fire Brigade said:

‘If the cladding hadn’t been there then the fire definitely wouldn’t have spread that quickly. Usually, in tower fires, the concrete levels act as a sealed lock to contain the fire, but this has not happened here.’

But if this tells us something about how the residents of Grenfell Tower died, it still doesn’t tell us why it was that this 24-storey tower block in the Notting Barns ward of North Kensington was fitted with a cladding system that architect and fire safety expert Sam Webb described to the Guardian as ‘a disaster waiting to happen’.

2. Management Decisions responsible for the Grenfell Tower Fire

Grenfell Tower is part of the Lancaster West estate, the rest of which is made up of three 5- and 6-storey finger blocks between which lie landscaped gardens. Before the council took the land away from them to build the new Kensington Aldrige Academy secondary school – for which the refurbishment that killed the residents was offered as a form of compensation – there were several football grounds and other games courts to the north of the tower. When construction was completed in 1974 the original estate would have been a paradise to the tenants fortunate enough to be housed there. And rather than a ghetto for the poor that council estates have subsequently been denigrated as, the community included a mix of social classes. Grenfell Tower was built to Parker Morris Standards, with the top 20 storeys containing 120 flats. Built around a central core containing the lift, staircase and vertical risers for the services, each floor had four 2-bedroom and two 1-bedroom flats, making a total of 200 bedrooms. Communal facilities included a nursery on the first floor (or mezzanine level) and the Dale Youth amateur boxing club, which moved into the ground floor of Grenfell Tower in 2000. As part of its refurbishment in 2016, both nursery and boxing club were relocated, respectively, to the ground and third floor (or walkway level), and an additional six 4-bedroom and one 3-bedroom flats added on the first and fourth floors. This brought the total number of flats in Grenfell Tower up to 127, and the number of bedrooms to 227.

In an interview in June 2016 with Constantine Gras, an artist who was commissioned by the Kensington and Chelsea Tenant Management Organisation to make a film about the refurbishment, Nigel Whitbread, the architect of Grenfell Tower, said of its original construction:

‘Ronan Point, the tower that partially collapsed in 1968, had been built like a pack of cards. Grenfell Tower was a totally different form of construction, and from what I can see could last another 100 years. I’m very much against knocking things down unnecessarily. I had heard that there had been problems a few years ago with the heating and that it was no good, and talk of the whole block having to come down. And I thought: if my heating goes wrong, I don’t want to pull my house down!’

Grenfell Tower Management

In 1996 the entire council housing stock of the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea was transferred to the Kensington and Chelsea Tenant Management Organisation (KCTMO), which currently manages 9,459 properties, of which around 6,900 are tenant-occupied and 2,500 leasehold properties, and from which it collects £44 million in rent and £10 million in service charges every year. The KCTMO is unique in also being an Arms Length Management Organisation (ALMO), which means that activities between it and the council are viewed by Her Majesty’s Revenue and Customs as non-trading activity, so any profit arising from it will not be taxable. KCTMO has a board which at the time of the Grenfell Tower fire comprised eight residents, three council-appointed members and two independent members. Their identities have now been removed from the company website, but at the time of the fire they included:

- Fay Edward, the Chair and Resident Board Member since 2012 and recipient in the Queen’s New Year’s Honours List 2015 of the British Empire Medal. It was she who awarded the contract for the fatal refurbishment of Grenfell Tower;

- Conservative councillor Maighread Condon-Simmonds, the Lady Mayor of the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea until May 2017;

- Labour councillor Judith Blakeman, who sits on the council’s Housing and Property scrutiny committee, and who in December 2015 dismissed calls by the Grenfell Action Group to investigate the KCTMO;

- Council-nominated Board Member Paula France, a former employee at the government’s Homes and Communities Agency who has held senior positions in Circle, Thirty Three, Look Ahead, Network Housing and Shepherd’s Bush housing associations and now runs her own consultancy business;

- Independent Board Member Simon Brissenden, a Management Consulting Professional who until March of this year was employed to deliver Health and Safety Compliance in the Asset and Investment portfolio for Genesis Housing Association;

- Independent Board Member Anthony Preiskel, since 2012 a Non-Executive Director of the government’s Homes and Communities Agency.

The KCTMO is not a co-operative, which means that although it was created under the government’s Housing (Right to Manage) Regulations 1994, it was set up under corporate law. And although the housing stock it manages is still owned by the council, as an ALMO (the only UK TMO, apparently, that is also an ALMO) it is exempt from Freedom of Information requests (not that councils answer these either, or when they do the information requested is redacted). The distinction between public and private means very little these days, and one look at who sits on this board shows that it’s run by housing professionals fronted by politicians with the acquiescence of compliant residents – in other words, the same privatised management structure being put in place for every other estate regeneration scheme in London.

Grenfell Tower Refurbishment

As this diagram from the Guardian illustrates (below), Artelia UK, which specialises in cost management, was contracted by KCTMO to be project managers on the Grenfell Tower refurbishment, which was carried out in 2016. On its website page on residential services, Artelia says that it ‘works closely with our clients to understand what success looks like to them and how we can make that success a reality’; and among its past experiences lists ‘refurbishment projects for local authorities.’ On its page on Health and Safety Management Artelia says it’s management results in a ‘safer, better, more cost-effective project.’ And on its page on Design and Construction Management Artelia says ‘we take full responsibility for architects, engineers, contractors and suppliers in a seamless process that drives out inefficiencies.’ Again, it cites its experience in working on programmes ‘where continuous reduction in construction costs is considered a non-negotiable contract deliverable.’ On the page describing its ‘involvement in the Grenfell Tower refurbishment project’ Artelia says that it was appointed as the ‘Employer’s Agent, Construction, Design and Management (CDM) Co-ordinator and Quantity Surveyor.’ Artelia describes the Grenfell Tower fire as a ‘tragic event.’

On the Designing Buildings Wiki page it says that the Construction, Design and Management Co-ordinator (CDM) role is to:

- ‘Advise the client on matters relating to health and safety during the design process and during the planning phases of construction.’

- ‘Notify the health and safety executive of the particulars specified in schedule 1 of the regulations.’

- ‘Advise the client as to the adequacy of resources.’

- ‘Co-ordinate health and safety aspects of design work.’

- ‘Advise on the suitability, co-ordination and compatibility of design in relation to health and safety.’

- ‘Advise on the adequacy of the construction phase plan before construction works begin.’

- ‘Advise on the adequacy of any subsequent changes to the construction phase plan.’

- ‘Prepare or compile the health and safety file and issue it to the client at the end of the construction phase.’

So far, therefore, Artelia seems to be the company responsible for the health and safety of the refurbishment of Grenfell Tower, its design, planning, compatibility with the existing building, construction and materials used.

However, on 6 April 2015, the year before the refurbishment of Grenfell Tower began, the Construction, Design and Management Regulations were changed, with the role of the CDM Co-ordinator transferred to a Principal Designer, which is responsible for the pre-construction phase, and a Principal Contractor, which is responsible for the construction phase. Under the new CDM regulations the client, which in this project was Kensington and Chelsea TMO, is responsible for ‘ensuring that both the Principle Designer and Contractor are complying with their duties, and for making Health and Safety Executive notification.’ However, as an article on these changes published in the Architects’ Journal observes: ‘this may be difficult where the principal designer has no direct contractual authority over [the other designers].’ In effect, the article concludes, the role of the CDM Co-ordinator has been abolished. As Quantity Surveyor for the project, therefore, Artelia was responsible not for ensuring Health and Safety regulations were met in the refurbishment, but for reducing the costs of refurbishment.

The Principal Designer and Principal Contractor on the refurbishment of Grenfell Tower were, respectively, Studio E Architects and Rydon, a construction, development, maintenance and management group. In response to the Grenfell Tower fire, Studio E Architects, which as we said has removed its webpage on the Grenfell Tower refurbishment, has written that it will be ‘ready to assist the relevant authorities as and when we are required.’ Despite the fatal design fault which, as we have seen, effectively turned the cladding into a vast chimney for the flames, Studio E also describes the Grenfell Tower fire as a ‘tragic incident.’ Rydon, which also describes the fire as a ‘tragedy’, has also removed its webpage on the refurbishment, and replaced it with a statement about Grenfell Tower saying:

‘Rydon Maintenance Limited completed a partial refurbishment of the building in the summer of 2016 for KCTMO on behalf of the Council, which met all required building regulations – as well as fire regulation and health and safety standards – and handover took place when completion notice was issued by Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea building control.’

This Completion Certificate for the refurbishment work on Grenfell Tower, issued on 17 July, 2016 by John Allen, the Kensington and Chelsea Building Control Manager, reads:

‘The Council hereby certifies under Regulation 17 that as far as could be ascertained, after taking all reasonable steps, the building work carried out complied with the relevant provisions. This certificate is evidence, but not conclusive evidence, that the relevant requirements specified below [Schedule 1] have been complied with.’

This is equivocal enough. But the Kensington and Chelsea council website page on the refurbishment work to Grenfell Tower (application FP/14/03563) also lists the status as: ‘Completed Not approved’. No date is given for this decision. However, in an ‘Important Update’ to this page, the council adds this addendum:

‘People searching for application FP/14/03563 please note that the status “Completed Not approved” does not mean that the work was not approved under the Building Regulations. The formal signing off of the work was provided by a Completion Certificate and not by a Full Plans decision notice, which was not required in this case. The system status “Not approved” appears because a decision notice was not issued. However, a completion certificate was issued signing off the works under the Building Regulations.’

So, who is responsible for fitting Grenfell Tower with flammable insulation and a combustible cladding system that acted as a chimney for the fire?

Grenfell Tower Responsibilities

In response to the Grenfell Tower fire, ASH received several e-mails from a senior architect who wishes to remain anonymous, but who gave us permission to publish his comments, which we include at length here:

‘If, as has been reported in the Guardian, the design of the cladding was different to that which was detailed in planning documents, were the architects (Studio E), in charge of the refurbishment works under a traditional building contract? That is unlikely. In the climate of Private Finance Initiative design-and-build contracts, the architects are engaged only to add gloss to the project marketing – to raise the Right-to-Buy value of the property under the coinage of “architect designed”. If the architects were not in charge of enforcing compliance with contract specifications, then they would have been cut to the bone by the contractor to maximise every penny of profit. PFI contracts are bought and sold on the open market like any other commodity.

‘Regardless of the route to compliance with Building Regulations, on completion of the works the conformance authority, in this case Kensington and Chelsea Building Control, must issue a Completion Certificate, without which the refurbished building cannot be insured – for example, for fire.

A further e-mail continued:

‘There are two things here: 1. The insulation fixed over the existing external walls; and 2. The cladding fixed on top of that, with a gap between the two. The cladding has a material which is the sandwich fill between the two layers of thin aluminium. If we are talking about the second issue, the cladding, no one in their right mind would specify the combustible type, partly because of case law, where architects who did specify that lost their defence at appeal in the High Court in 2003. You might as well clad the building in ten-pound notes dipped in Napalm.

‘The Principal Designer (in this case Studio E Architects) would normally seek written advice from the supplier – with a quote for supply – that the material is fit for purpose. In this case it is inconceivable that the manufacturer of Reynobond (Arconic Europe) would not recommend their “A2 Fire Solution”, comprising an incombustible sandwich core that conforms with European fire certification EN 13501-1, class A2.

‘However, in PFI and design-build projects, the designer is not in charge of the job. Instead, an unregulated yes-man, or yes-woman, is employed to deliver the project. The contractor (in this case Rydon) submits a price, and the public employer (in this case KCTMO) will select the lowest in the interest of the public purse. The contractor (Rydon) has in mind ways to cut costs to maximise profit on tight margins, while the designer (Studio E Architects) wants to protect the quality of the build. So the procurement process can be adversarial.

‘The local authority (Kensington and Chelsea council) has a statutory role to inspect and approve that the materials and construction conform to regulations. Frequently, these days, private firms can do this, and are generally better and more efficient than a local authority. In the case of Grenfell Tower the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea (RBKC) Building Control were responsible, but the contractor chose not to submit Full Plans of construction details for approval; rather, they relied on site inspections – presumably in order to accelerate the project, but, one might argue, also in order to avoid having to commit construction details and material specifications documentation to the record.

‘Because of the nature and scale of the project, it is unusual for the Building Control department to accept Building Notice at all. It would have been better had they insisted on Full Plans submission, especially because there were architectural drawings available. So there is a question that points to a “chemistry” between the contractor and the Building Control department.

‘Around the world – for example, in France – it is mandatory to have a registered architect and/or Maitre d’ouvres, or Architect of Record, in charge of all construction projects over a minimum threshold size of 70m2. In Britain that isn’t the case. The perception is that an architect’s appointment adds onerous unnecessary cost, so the delivery of the building works is reliant on the trust and integrity of the builder, and on effective Building Control site inspection that what is carried out is compliant. In this case, and countless others procured under Private Finance Initiative terms, that failed.

‘Since PFI was introduced by Thatcher we have a legacy of hundreds, if not thousands, of sub-standard buildings – schools, hospitals, police stations, etc – that the taxpayer is still paying extortionate rents for under the terms of the 30-year lease-back deal that is PFI. This is her legacy of cosy relationships between local authorities, quangos and their chummy contractors. It is a culture of de-regulation, of private profit before public good. Thomas Dan Smith, the Leader of Newcastle City Council from 1960 to 1965, went to gaol in 1974 for dodgy dealings with local authorities in property development, albeit from a different motivation; but what the public must demand and get now over the Grenfell Tower fire are criminal convictions, and soon.’

3. Political Context for the Grenfell Tower Fire

So much for those responsible for the deadly refurbishment of Grenfell Tower; but why was it deemed necessary to clad the tower in the first place and who made that decision?

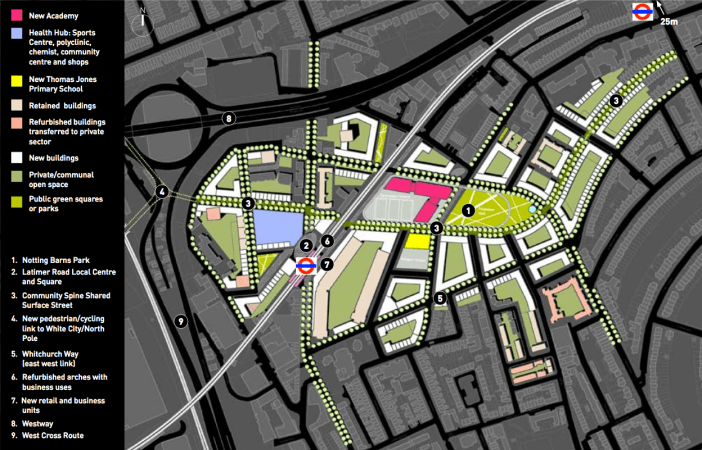

Grenfell Tower Regeneration

In February 2009, eight years before the Grenfell Tower fire, Urban Initiatives Studio, a practice specialising in urban design, planning and change management, was appointed by the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea to create a masterplan for the regeneration of Notting Barns South, an 18 hectare site in North Kensington containing the Silchester and Lancaster West estates, including Grenfell Tower. 6 months later they produced Notting Barns South: Draft Final Masterplan Report, which included the following observations and recommendations, beginning with this Executive Summary:

‘The area suffers from housing stock in need of ongoing and expensive refurbishment, a range of social deprivation and other issues often associated with large post-war housing estates. This context means that land values are artificially depressed closer to the centre. The Far-sighted Option aims to maximise overall value in the long term and create a high quality new neighbourhood. This requires a number of significant interventions. We estimate that the project could deliver significant returns to the council. In order to present the most attractive offer in a competitive bidding process the winning consortium would need to adopt the most optimistic approach to cost and/or values.’

To back up the necessity of the council adopting their proposals, the report also addresses what it calls Issues and Opportunities, the former of which include the following:

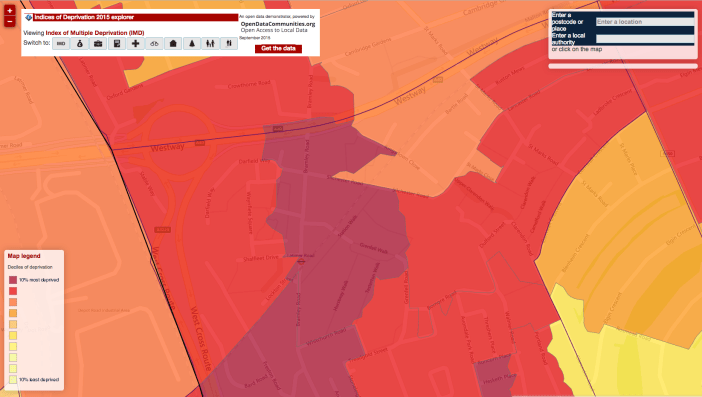

‘Although a diverse population in terms of age, ethnic and religious backgrounds, the area is limited in terms of its economic profile and is predominantly made up of social housing tenants. The ward of Notting Barns South suffers substantial issues of deprivation relating to employment, health and crime, however, the intensity of deprivation varies. The Lancaster West estate (east) is within the 10 per cent most deprived areas in the country, and similarly crime is more severe in the east of the study area.’

Now, in fact, as shown by these two screen grabs (below) from the Indices of Deprivation 2015 interactive map, although Lancaster West estate does lie within the 10 per cent most deprived areas (left), its crime rates are shared by 40 per cent of areas (right), and is in fact far lower than in surrounding areas where terraced housing predominates. This accords with the figures on every estate ASH has researched, from Broadwater Farm to Aylesbury and Central Hill. Behind the unsubstantiated and easily-accepted assertions of reports like this one, crime levels on council estates are in fact consistently lower than in the surrounding area, contradicting everything we are told about council estates and their communities by terrace-dwelling journalists and developer-lobbied politicians. Not only are estates not ‘breeding grounds’ for crime, as they are characterised in both Fleet Street and Westminster, but the close-knit communities that form within them significantly reduce crime rates. As in just about everything else being said about council estates in the wake of the Grenfell Tower fire, estates as homes to anti-social behaviour, crime and drug dealing is another myth that is being used by architects, developers, councils, journalists and politicians to promote estate demolition, privatisation and redevelopment.

In the Urban Initiatives report, particular attention is given to the development options on the towers in the area, starting with the four 22-storey towers on the Silchester estate:

‘It would be very challenging for the scheme to reprovide this number of homes should they be demolished. Therefore our preferred approach is to assume retention and refurbishment. In certain cases it may be possible to transfer these towers to private sector developers to provide private sale or rent units.’

Grenfell Tower, by contrast, has no such reprieve:

‘We considered that the appearance of this building and the way in which it meets the ground blights much of the area east of Latimer Road Station. It also provides no outdoor space for residents and is likely to be of a type of construction that is hard to adapt. It does contain 120 homes. On balance our preferred approach is to assume demolition.’

The report goes on to outline the Phasing and Delivery of the proposed 15-20-year masterplan, from which we have extracted the following:

Phase 1. ‘Includes the construction of the new school immediately to the east of the railway line on the existing Games Court and Kensington Sports car park. Adjacent to the station two private 12-storey towers are erected.’

Phase 2. ‘East of the railway the eastern part of Lancaster West is demolished together with Grenfell Tower. This building blights the area, provides no outdoor space for residents and is difficult to refurbish. The remainder of Lancaster, which is being refurbished, is completed into a closed street block with infill development. By the end of this phase the regeneration of the Silchester and Lancaster area is almost complete.’

Citing the area as providing no outdoor space for residents as a justification for the demolition of Grenfell Tower in Phase 2 is ironic at best given that Phase 1 began with building the Kensington Aldrige Academy – which was also designed by Studio E Architects – on that outdoor space, thereby taking it away from residents; but like the stereotypes about crime in the area this doesn’t halt the concluding phases, when the ‘Far-sighted Option’ that aims to ‘maximise the overall value’ of the area comes into its own:

Phase 3. ‘This phase realises a large proportion of high-end, high-value market housing.’

Phase 4. ‘New housing can benefit from the proximity to and overlooking of the park, and market housing is expected to realise increased values.’

Phase 5. ‘During this phase 610 units are developed or refurbished with a high percentage of private units.’

All of which leads the authors of this report, Matthias Wunderlich, Stuart Gray and Dan Hill, to the following conclusions:

‘The farsighted option for the masterplan presented within this report has the potential to transform the social and physical characteristics of Notting Barns in a positive manner. Because of the existing tenure mix and the decline of Right to Buy, the estate will never become a more mixed and integrated community. This work shows how sensitive the potential residual land values are to residential sale values and, in particular, to the potential values for high end flats and houses. To achieve the highest values, the area will need to undergo significant change to improve its visual appearance.’

Grenfell Tower Appearance

Following the financial crash, house prices in London in 2009 had fallen for the first time in decades; and presumably for this reason, which may have dissuaded development partners, Kensington and Chelsea council declined the ‘Far-sighted Option’ (above) and chose, instead, what the report called the ‘Early Value Option’ (below). In its broad outlines this is the masterplan which, updated in May 2016 by CBRE building consultancy, continues to threaten the residents of the Silchester estate with the demolition and redevelopment of their homes – the most recent plans for which were exhibited in April 2017 – and has already built the Academy on the playing fields, but which also refurbished Lancaster West estate, including Grenfell Tower. The reason for doing so, however, had not changed from that which targeted it for demolition as a ‘blight’ on the area – that is, its appearance.

The 2014 planning application (ref. PP/12/04097/Q18) for the refurbishment of Grenfell Tower reads:

‘The materials proposed will provide the building with a fresh appearance that will not be harmful to the area or views around it. Due to its height the tower is visible from the adjacent Avondale Conservation Area to the south and the Ladbroke Conservation Area to the east. The changes to the existing tower will improve its appearance especially when viewed from the surrounding area. Therefore views into and out of the conservation areas will be improved by the proposals.’

The planning considerations listed include: ‘The impact of the works on the appearance of the building and area, and views from the adjacent conservation area.’ The materials used on the external faces of the building used were chosen ‘To accord with the development plan by ensuring that the character and appearance of the area are preserved and living conditions of those living near the development suitably protected’. While the windows and doors were chosen ‘To ensure the appearance of the development is satisfactory. The re-clad materials and new windows will represent a significant improvement to the environmental performance of the building and to its physical appearance.’ The application concludes: ‘The changes to the external appearance of the building will also provide positive enhancements to the appearance of the area.’

On the webpage (now removed from their site) where Grenfell Tower was listed as a case study, Rydon wrote: ‘Rain screen cladding, replacement windows and curtain wall façades have been fitted giving the building a fresher, modern look.’ And Nicholas Paget-Brown, the now ex-Leader of Kensington and Chelsea Conservative council, is quoted on the council webpage on the refurbishment as saying: ‘It is remarkable to see first-hand how the cladding has lifted the external appearance of the tower.’

Studio E Architects’ webpage on Grenfell Tower – again, sent to us by an architect before it was taken down – shows an artists’ impression (below) for the client of what the refurbishment would look like, complete with the white, middle class residents drawn to attract investors into the area, and who are so at odds with the racial and class demographic of the tower revealed by the hundreds of photographs of missing residents put up around the burnt out carcass of the building by families and friends. This is the external view of the Grenfell Tower for which the people who lived inside the building died.

Grenfell Tower Profits

Nicholas Paget-Brown became the Leader of Kensington and Chelsea Conservative council in May 2013, when residents of Grenfell Tower first began complaining about fire safety in their block. He has been a councillor in the borough since 1986, and previously occupied the position of Cabinet Member for Community Safety, Regeneration and the Voluntary Sector, in which capacity he was responsible for driving a range of capital investment projects in North Kensington. A former City marketing manager for the international news agency Reuters, Paget-Brown is currently Managing Director at Pelham Research, which analyses government policy and offers management briefings on public policy for businesses and local authorities.

The Deputy Leader of the council, also appointed in May 2013, as well as Cabinet Member for Housing, Property and Regeneration, is Rock Feilding-Mellen, who owns a £1.2 million 3-storey townhouse in the ward. Having lost the St. Charles ward, where he had been councillor since 2006, Feilding-Mellen was parachuted into the Holland ward in 2010. He was subsequently made Cabinet Member for Civil Society, which meant he was responsible for the council’s policies on community safety, economic development, the voluntary sector and community engagement. Until becoming Deputy Leader, Feilding-Mellen also sat on the Major Planning Development Committee. In addition to his responsibilities on the Kensington and Chelsea council, Feilding–Mellen is also the Leader’s Committee Deputy, Lead Member for Economic Development and Regeneration, Lead Member for Housing, and Lead Member for Employment and Skills for London Councils, the cross-party local government association, think-tank and lobbyist for Greater London. In his spare time Feilding–Mellen is also the Director of property developers Socially Conscious Capital Ltd, Director of SCC Longniddry Ltd, Director of Vilnius Investment Management Ltd, and Director of UAB May Fair Investments, a real estate company registered in Lithuania.

In 2016 both Nicholas Paget-Brown and Rock Feilding-Mellen attended MIPIM, the world’s leading international fair for property professionals in Cannes, where London councils – among other landlords – agree deals with property developers for the land on which residents in their boroughs are still living. In the wake of the Grenfell Tower fire, both Paget-Brown and Feilding-Mellen have resigned from their Cabinet positions, although not as councillors, the former saying in his resignation statement that he has to ‘accept my share of responsibility for these perceived failings’. Both men described the Grenfell Tower fire as a ‘tragedy’.

Nicholas Holgate was appointed Chief Executive and Town Clerk of Kensington and Chelsea council in December 2014. A career public servant who was previously Chief Operating Officer at the Department for Culture, Media and Sport, Holgate joined the borough in 2008 as Executive Director for Finance, Information Systems and Property. In 2016-17 Holgate’s salary was £187,780, with a bonus of between 3 and 10 per cent based on performance. For this he was expected to work 4½ days per week. In the wake of the Grenfell Tower fire Holgate was compelled to resign by Sajid Javid, the Secretary of State for Communities and Local Government. However, the Daily Telegraph has reported that Holgate will be entitled to compensation for losing his job, understood to be equivalent to at least six months’ pay, or around £100,000.

Robert Black, a former Executive Director of Services at Circle Housing Group, was appointed Chief Executive of the Kensington and Chelsea TMO in 2009. He too has resigned in the wake of the Grenfell Tower fire – according to an announcement by the KCTMO board, ‘in order that he can concentrate on assisting with the investigation and inquiry.’ Together with Barbara Matthews, the Executive Director of Financial Services and Information and Communication Technology, Yvonne Birch, Executive Director of People and Performance, and Sacha Jevans, Executive Director of Operations, Black was part of a team of ‘key management personnel’ which, according to the latest accounts filed by the KCTMO with Companies House, collectively earned £760,000 last year. In accounts for the financial year ending March 2016, KCTMO’s income was £4.42 million, with a turnover just over £17.6 million.

The Times has reported that documents from June and July 2014 reveal that KCTMO sent an ‘urgent nudge e-mail’ to Artelia UK, the project managers on the Grenfell Tower refurbishment, saying that they had a meeting the next morning with Councillor Feilding-Mellen, who was overseeing the refurbishment. The e-mail reads: ‘I have been reminded that we need good costs for Cllr Feilding-Mellen and the planner tomorrow at 8.45am!’ The e-mail went on to list three options for reducing the cost of cladding. One of these was to use panels made of combustible and flammable aluminium with a polyethylene core rather than a non-combustible zinc with a mineral-rich fire-retardant core that was proposed by Studio E Architects and approved by residents in 2012. This swap, which was made after tender, could mean, the e-mail says, ‘a saving of £293,368’. Asked about these e-mails, Artelia responded that it is ‘bound by a duty of confidentiality in its contract with KCTMO.’

According to a report in the Guardian, the BCM glass reinforced concrete (GRC) panels that were used to clad the columns on the ground floor of Grenfell Tower have the highest fire rating of A1, and have been used on luxury apartment complexes, including high rises. However, industry sources said glass reinforced concrete panels cost around twice as much as the polyethylene aluminium panels used on the rest of the building, and would have increased the refurbishment costs by at least £1 million.

The Reynobond PE panels used on Grenfell Tower are prohibited on high-rise buildings in the USA and, according to the Department for Communities and Local Government, also breach the UK’s Building Regulations 2010, which restrict their use on buildings over 18 metres tall. Arconic, the company that manufactures Reynobond PE, has published guidelines warning that the PE cladding is unsuitable for buildings above 10 metres tall, and even the FR cladding is only suitable up to 30 metres, after which it advises that the non-combustible A2 model should be used. Despite this, e-mails obtained by Reuters show that in July 2014 Deborah French, Arconic’s UK sales manager, and executives at the contractors involved in the bidding process for the refurbishment contract, were involved in discussions about the use of cladding on Grenfell Tower, which is 60 metres tall. Asked about these e-mails, Arconic, which has since discontinued the sale of Reynobond PE on high-rise buildings, replied that ‘it was not its role to decide what was or was not compliant with local building regulations.’ In its 2016 brochure on ‘Fire safety in high-rise buildings’, Arconic warned:

‘When conceiving a building, it is crucial to choose the adapted products in order to avoid the fire to spread (sic) to the whole building. Especially when it comes to facades and roofs, the fire can spread extremely rapidly.’

The reductions in cladding costs were among savings of £693,000 required by the Principal Contractor, Rydon, which won the contract in June 2014 by undercutting estimates from the original contractor. The Leadbitter Group had estimated the project in 2012 at a cost of £11.3m, considerably higher than Kensington and Chelsea council’s target budget of £9.7 million. Rydon offered to do the refurbishment for £8.7 million, and were awarded the contract, according to a report by Kensington and Chelsea’s housing and property scrutiny committee, following a ‘value engineering process’. Last year Rydon made a pre-tax profit of £14.3 million on revenues of £271 million, and paid investors a dividend of £2 million, the largest slice of which went to Rydon’s Chief Executive and largest shareholder, Robert Bond, who also earned a salary of £424,000, a pay rise from £392,000 the year before.

In 2015 Harley Curtain Wall won the £2.6 million contract from Rydon to install the Reynobond PE panels. But after being pursued for almost £2.5 million by HM Revenue & Customs for involvement in alleged tax-avoidance schemes the company went into administration later that year, before the work had been completed. However, Managing Director Ray Bailey was allowed to purchase his old business for just £24,900 and continue trading under the new name of Harley Facades. The company has since removed all details about the contract from their website ‘as a mark of respect to the people of Grenfell Tower.’

At the time of the fire, Kensington and Chelsea Conservative council had £283 million in its reserves – although it has since claimed that the Housing Revenue Account, whose management is delegated to the KCTMO, only contained £21 million. This didn’t stop the council from offering rebates to borough residents who were paying the top rate of council tax. According to figures released under the Freedom of Information Act and published in the Observer, as of spring 2016 the Conservative council has moved 1,668 homeless households living in temporary housing outside the borough – the joint highest figure in England alongside fellow London council Newham, which is Labour-run. Of those households, 902 had been ‘temporarily’ rehoused outside Kensington and Chelsea borough for at least a year – the second highest such figure in the country. Hundreds more have been sent to outer London boroughs such as Barking and Redbridge, or outside London altogether, to Kent and Essex. The latest figures for Kensington and Chelsea council reveal that, as of March 2017, the council only has 433 properties for let in a borough with around 1,000 homeless households living in temporary accommodation. It also had 2,677 households on the housing waiting list in 2014, a drop from 8,493 households just a year earlier. This reduction, which is representative of London councils, follows the introduction of the 2011 Localism Act, which radically changed both the criteria by which households qualify for council housing and the duty of care the council has to house them. A survey by Inside Housing in March 2016 found that, since the Localism Act came into effect in June 2012, 159 English councils had struck 237,793 people off their waiting lists and barred a further 42,994 new applicants. Meanwhile, a BBC report has revealed that, under Section 106 agreements in the Town and Country Planning Act 1990, Kensington and Chelsea council accepted £47.3 million from developers in lieu of affordable housing in 2016 alone, with just 336 affordable units having been built in the borough since 2011.

In contrast to this demand for housing, the failure to build it, and the relocation of homeless households outside the borough, the latest figures for Kensington and Chelsea reveal that, as of July 2017, there are 1,857 vacant private dwellings in the borough. 111 of these are classified as unoccupied and substantially unfurnished; 50 as unoccupied with works in progress for less than 12 months; and 696 as empty for more than 2 years. In a report published by the council’s Housing and Property Scrutiny Committee in July 2015, it was found that of the 941 dwellings then classified as unoccupied – half the current number only two years ago – around 50 had stood empty for between 11 and 15 years. And as shown by Private Eye’s interactive map of properties in England and Wales acquired by overseas companies between 2005 and 2014, most of these are registered to companies based in tax havens like the Virgin Islands.

To address this, a tax on vacant homes such as Vancouver, for example, has recently introduced to address the housing crisis in Canada would be a start; but it’s not likely to deter offshore companies registered in tax havens. We need new legislation compelling a dwelling to be used as such, and giving those in need of housing the right to occupy – and if necessary pay council rent on – empty properties. For a start, the laws on squatting, which were altered in 2012 in anticipation of the thousands of empty properties London now has, need changing. Under section 144 of the Legal Aid, Sentencing and Punishment of Offenders Act 2012, properties classified as residential, no matter how long they have stood empty and unused, cannot be legally squatted, and to do so is now a criminal offence punishable by up to 51 weeks imprisonment. As a result, as of February 2016 – not including the City of Westminster, which refused to supply numbers but where where 1 in 10 properties are owned by off-shore companies – more than 22,000 properties in London have been left empty for more than six months. More than a third of these, 8,560 properties, have been empty for over two years; and 1,150 properties have been empty for over a decade. This in a city where 250,000 households are on council housing waiting lists; 240,000 households with 320,000 children are living in overcrowded accommodation; and over 53,000 households with over 90,000 children are homeless and living in temporary accommodation. But to free up properties purchased for their exchange value and make them available for the use of the people who need them, a more fundamental change in our laws needs to happen, whereby the rights of people to use a property as a home takes precedence over the rights of ownership over that property. That’s only ever going to happen, though, through mass occupations of empty properties following – for example – a disaster that makes hundreds of people homeless in one of the wealthiest boroughs in the UK.

There was nothing wrong with either the original design or build of Grenfell Tower. Four decades of developer-led housing policy, government cuts to local authority budgets, the financialisation of housing in the UK, the managed decline of our estates by councils preparatory to their demolition and redevelopment as properties for capital investment, the privatisation of council housing management through ALMOs, TMOs and the stock transfer of council estates to housing associations, the unaccountability of local authorities increasingly run as private fiefdoms by councillors who are little more than lobbyists for the building industry, and the recourse to Private Finance Initiatives to build housing whose safety is subordinate to the profits of developers, builders, architects and estate agents getting rich on the UK’s housing crisis – that’s what killed the residents of Grenfell Tower, not its architecture.

4. The Fire Safety of Council Tower Blocks

Out of the 600 tower blocks over 18 metres tall and fitted with cladding that are undergoing tests in the wake of the Grenfell Tower fire, 181 council-owned blocks in 51 local authorities across England have failed to meet the necessary standard of fire resistance as of 2 July, with a 100 per cent failure rate on those tested. In London alone this number includes 3 tower blocks in the borough of Barnet, 2 in Brent, 5 in Camden, 1 each in Hounslow, Islington and Lambeth, 2 in Lewisham, 3 in Newham, 2 in Tower Hamlets and 2 in Wandsworth, a total of 22 tower blocks so far. Even then the tests, which are being carried out by the Building Research Establishment on behalf of the Department of Communities and Local Government, have been criticised for undertaking combustibility tests on the aluminium composite material in the rainscreen panels, while experts have warned that what determines how a fire spreads is the cladding support system, the insulation it protects, and the fire breaks in the cavity. What requires testing, therefore, is not only the combustibility of the various component materials, but how they respond to fire within the cladding system. In response to these criticisms, the government set up an independent Expert Advisory Panel that has advised the BRE to conduct 6 fire tests on 3 different cladding systems, comprising core filler materials of unmodified polyethylene, fire retardant polyethylene, and non-combustible mineral wool, each in combination with 2 different types of insulation, polyisocyanurate foam and non-combustible mineral wool. Potentially and probably, therefore, the number of tower blocks whose fire safety has been compromised by the addition of cladding to their exterior may be even higher. And there are fears that the tests will have to extend beyond the public sector into private tower blocks, as well as including universities, hospitals and care centres fitted with cladding. So how could such a widespread compromise of UK building fire safety have been allowed to happen?

Grenfell Tower Precedents

In July 2009 a fire started on the 9th floor of Lakanal House, a 14-storey block on the Sceaux Gardens estate in Camberwell, and quickly spread up 5 more floors of the building, killing 6 people. It later emerged that the block, which had been refurbished by Southwark council, had been fitted with a similar rainscreen cladding system as that which was later applied to Grenfell Tower by Kensington and Chelsea council. The 2013 inquest into the fire concluded that years of botched renovations had removed fire-stopping material between flats and communal corridors, and that this allowed the fire, which as in Grenfell Tower had started with an electrical fault, to spread both vertically and laterally, with the exterior cladding panels burning through in just four and a half minutes. A change in the law in 2006 meant Southwark council was responsible for fire safety checks in its flats, but by the time of the fire, 3 years later, the council had not carried out these checks at Lakanal House or any other residential block. This didn’t stop the council, however, from managing to carry out fire-safety checks at buildings where its own staff worked. In February of this year, at Southwark Crown Court, Southwark council, for its culpability in the safety failings at Lakanal House, was issued with a £270,000 fine (reduced from £400,000 because it had pleaded guilty) plus £300,000 costs – exactly £9,500 for every resident killed in the fire. Nobody was convicted.

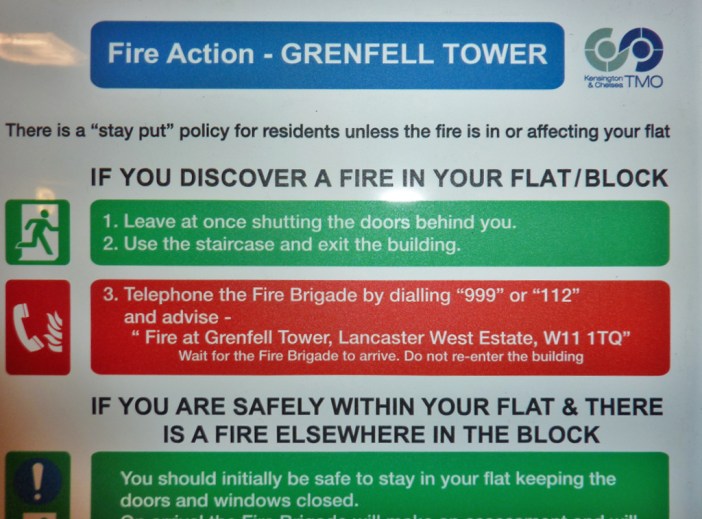

Following the Lakanal House fire the coroner’s report, which was sent to the Department of Communities and Local Government in March 2013, made a series of recommendations to the government, including that the Department provide national guidance to:

- ‘The “stay put” principle and its interaction with the “get out and stay out” policy, including how such guidance is disseminated to residents.’

- ‘Awareness that insecure compartmentalisation can permit transfer of smoke and fire between a flat or maisonette and common parts of high-rise residential buildings, which has the potential to put at risk the lives of residents or others.’

- ‘Encourage providers of housing in high-rise residential buildings containing multiple domestic premises to consider the retro fitting of sprinkler systems.’

- ‘Provide clear guidance in relation to Regulation B4 of the Building Regulations, with particular regard to the spread of fire over the external envelope of the building and the circumstances in which attention should be paid to whether proposed work might reduce existing fire protection.’

In his response to the coroner’s report, Conservative MP Eric Pickles, then the Secretary of State for Communities and Local Government, wrote that following the Lakanal House fire and deaths, in 2011 his Department had published detailed national guidance that:

‘Takes a practical approach to ensuring that those responsible for the safety of residents and others in purpose built blocks can take a comprehensive and pragmatic approach to managing risk effectively within the context of the Housing Act 2004 and the Regulatory Reform (Fire Safety) Order 2005. It addresses in some detail the rationale for the stay-put principle and provides detailed advice on the fire safety information that should be made available to residents in the light of the findings of a risk assessment.’

None of this guidance, therefore, took account of the recommendations of the Coroner’s Report published in 2013. To the coroner’s recommendation that sprinklers be retro-fitted in high-rise residential buildings, Pickles responded that: ‘My officials have recently written to all social housing providers about this.’ And on providing guidance on Approved Document B (fire safety) of Building Regulations with regard to how external cladding can reduce existing fire protection he wrote:

‘The design of fire protection in buildings is a complex subject and should remain, to some extent, in the realm of professionals. We have commissioned research which will feed into a future review of this part of the Building Regulations. We expect this work to form the basis of a formal review leading to the publication of a new edition of the Approved Document in 2016/17.’

An article in Construction News has revealed that in January 2012 a final impact assessment, titled Removing inconsistency in local fire protection standards, was published by Stephen Kelly, who was subsequently appointed Chief Operating Officer for Government and Head of the Efficiency and Reform Group, and Brian Martin, the Principal Construction Professional in the Building Regulations and Standards Division at the Department of Communities and Local Government, that recommended repealing 23 local building acts across England. Signed off by Andrew Stunell, then the Parliamentary Under-secretary of State for the DCLG and now House of Lords construction spokesperson, this document argued that the repeal of the acts was an ‘appropriate deregulatory measure that reduces procedural and financial burdens on the construction industry’. The assessment estimated that over a 35-year period, between £116,334 and £357,400 of capital savings could be achieved by not installing or maintaining sprinklers in tall buildings, and between £195,300 and £600,000 could be saved from not installing smoke extractors. In addition, it estimated that sprinkler maintenance could cost between £300 and £800 per building, and that implementing safety measures held within the local acts would add up to £1.1 million to the costs of a building over a 35-year period. Based on figures sourced from the Home Office on fire incidents between 1994 and 1999, and drawing on statistical research from a report published in 2005 by the Building Research Establishment – the same organisation that is conducting tests on the cladding systems of over 600 tower blocks – the final impact assessment concluded:

‘Local acts have no statistically significant impact as far as life safety aspects are concerned. For tall buildings there was little benefit, as the inherent degree of compartmentation is sufficient to prevent most fires getting too “big”.’

In December 2012 Eric Pickles announced the repeal of Sections 20 and 21 of the London Building Acts (Amendment) Act 1939, which contains legislation precisely on precautions against the danger of fire in buildings higher than 100 feet and the use of non-combustible materials and self-closing fire doors.

In August 2016 a fire broke out in Shepherd’s Court, an 18-storey tower block in Shepherd’s Bush, and spread rapidly up the outside of the building. In response to a Freedom of Information request by Inside Housing, the London Fire Brigade has since released the results of its investigation into the spread of the fire and the role played by the external panels, which were installed during window replacement work more than 10 years before. The report revealed that the panels were made of 17-23mm plywood board covered by blue polystyrene foam, 1mm steel sheet and decorative white paint:

‘As a fire develops and grows further, it is possible that a wide flame front could end up acting on the steel sheet of the panel. The heat from the flames would be conducted through the steel sheet and would therefore melt away the blue foam layer underneath. This would occur in a progressive fashion as the fire develops and would ultimately lead to the steel sheet not being held in place by sufficient bonded blue foam. The weight of the steel sheet would then ensure that it would become detached from the remainder of the panel (likely fall away) and expose the heat damaged blue foam and plywood layers to the developed flame front. This situation is likely to have occurred to the panels above the flat of fire origin when the living room windows of the flat of fire origin failed during the fire at this scene.’

Inside Housing requested further information from Hammersmith and Fulham council, including the panels’ fire protection rating, whether they are installed on any other buildings in the borough, plus a fire risk assessment for Shepherd’s Court – but the council refused the FOI request. The panels still appear to be fixed to Shepherd’s Court, with the exception of six floors on one side, where fire damage is still visible and tarpaulin sheets are draped across the building; and identical panels appear to be in use on three neighbouring towers, Bush Court, Woodford Court and Roseford Court.

Grenfell Tower Fire Warnings

In a 2014 report titled ‘Structural Fire Safety in New and Refurbished Buildings’ the London Fire Brigade warned of consequences of councils’ in-house Building Control departments having to compete against private contractors:

‘The fact that there is competition puts pressure into the system, by potentially diminishing rigour in an effort to win work. Some in-house teams express fear that their own council colleague project officers could choose other providers. Projects are signed off before they should be because of pressure for schemes to be completed.’

Over a year before the Grenfell Tower fire, Kensington and Chelsea council had been issued with fire safety Enforcement Notices in December 2015 and January 2016 for two of its other tower blocks following a fire at one of them, Adair Tower, a 14-storey block of 78 flats, that broke out in October 2015. Having examined the fire safety conditions in the block, the London Fire Brigade ordered KCTMO to provide self-closing devices on front doors and to improve fire safety in escape staircases in both Adair Tower and in a second block, Hazelwood Tower, that was built to the same design. These, however, were only 2 of the 43 Enforcement Notices on its properties Kensington and Chelsea council has received from the London Fire Brigade over the past three years since July 2014.